- Living In Croatia

- Croatian Recipes

- Balkan Recipes

Home > 33 Ancient Greek Archaeological Sites In Greece: The Acropolis & Beyond

33 Ancient Greek Archaeological Sites In Greece: The Acropolis & Beyond

Written by our local expert Gabi

Gabi is an award-winning writer who lives on the Island of Crete in Greece. She is an expert in Greek travel and writes guides for the everyday traveler.

This is your guide to the best archaeological sites in Greece that you have to see to believe. We uncover things from the Ancient Greek world and the Roman periods.

From the Acropolis in the city of Athens, Ancient Olympia, Akrotiri Excavations, and loads more of the most important ancient sites.

Greece is a magnificent country, home to pristine beaches and unique landscapes that will stick to your memory forever, making your holiday in Greece an unforgettable moment in your life.

One thing that makes the country truly unique is the fantastic variety of Archaeological sites you can visit in every corner of the country.

No matter where you are in Greece, a piece of history will always be waiting for you to discover and explore.

Skip Ahead To My Advice Here!

Archaeological Sites In Greece

In this article, we have included the best archaeological sites you can visit in the country. You can either visit them on your own or book a guided tour for better insight and more information. You can also get yourself a guide to each site to explore better.

- Acropolis of Lindos in Rhodes

- Acropolis, Athens

Ancient Agora, Athens

- Ancient and Medieval Rhodes

- Ancient city of Aigai (Also known as the UNESCO Archaeological Site of Aigai in Vergina)

- Ancient city of Corinth

- Ancient Delos Archaeological Site and Museum

- Ancient site and museum of Mycenae

- Ancient site and theatre of Epidaurus

- Ancient Temple of Apollo Epicurius

- Ancient Temple of Poseidon, Cape Sounion

- Archaeological Site and Museum of Ancient Delphi

- Archaeological Site of Philippi and ruins of Macedonian city Krinides

- Archaeological site and Museum of Olympia

- Archaeological site of Akrotiri in Santorini (Also known as Akrotiri, Minoan Bronze Age settlement)

- Archaeological site of Gortyna, Crete

- Archaeological site of Phaistos, Crete

- Archaeological site of Sparta

Archaeological Site of Eleusis (Elefsina)

- Catacombs in Milos

- Delphi, Central Greece

Meteora, Central Greece

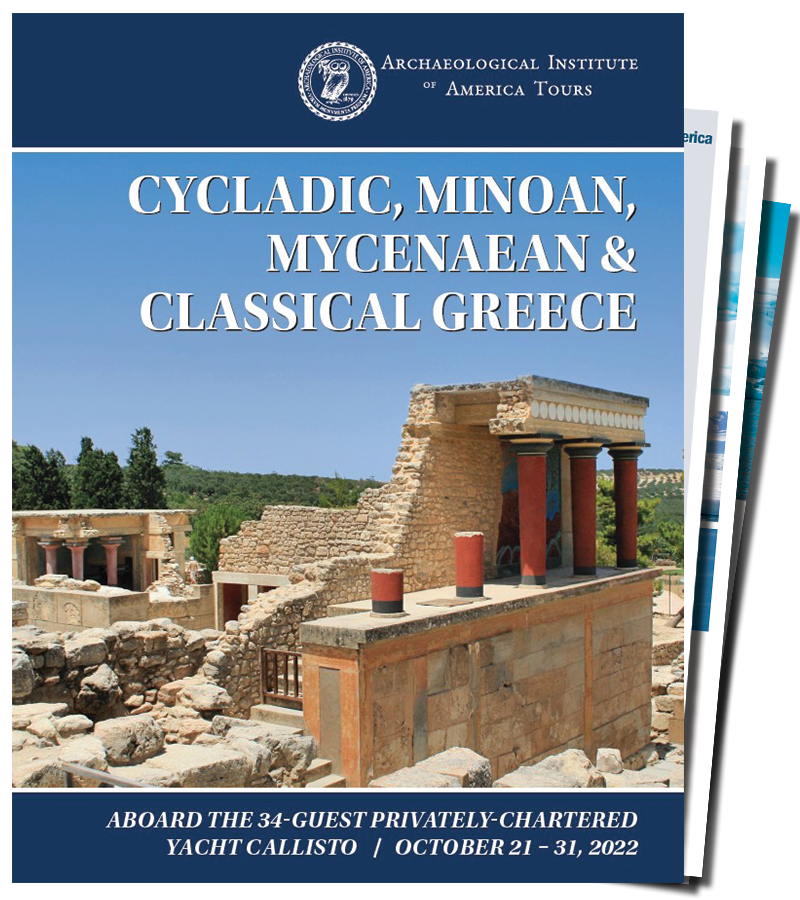

- Minoan Palace of Knossos in Crete

- Mycenae, Peloponnese

- Mystras, Peloponnese

- Olympia, Peloponnese

- Paleochristian and Byzantine Monuments, Thessaloniki

- Pythagoreion and Heraion, Samos island

- Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus

- Temple of Poseidon at Sounion

- The Ancient City of Thebes

- The fortified islet of Spinalonga in Crete

- The Royal Tombs at Vergina

Let’s see where the most spectacular Greek archaeology sites you can visit are located;

Most Visited Sites Archaeological Sites Of Greece

The acropolis in athens – highest point of the city.

The most famous and most visited archaeological site in Greece is the Acropolis of Athens . Usually crowded all year long, it’s a must-visit site in Greece, and you cannot miss your itinerary of heading to the island’s capital.

Also known as the Sacred Rock, the archaeological site overlooks the whole site of Athens as it is the highest point of Athens. The Acropolis is the most remarkable heritage of the Classical period and one of Europe’s most prominent ancient monuments.

The buildings in the site date back to the 5th century BC and are the most imposing living memory of Ancient Athens’s former splendor. The main building is its Parthenon temple, an architectural marvel of all times. Other buildings to check in on the site include the Temple of Athena Nike and the Erechtheion.

Tips for visiting: The site is usually extremely crowded, but this shouldn’t stop you from visiting. Book your tickets in advance, pay a bit more for a skip-the-line option, or visit every early in the morning or right before sunset for a less overcrowded experience.

Remember that the marbles you’ll be walking on are ancient; they’ve been worn by the elements, so they are slippery. Wear the right shoes and carry a refillable water bottle if you visit during the hottest hours of the day.

If you’re visiting Athens and plan to discover the wonders of the Acropolis , choose a hotel in the area. Great options are the Herodion Hotel and AthensWas.

Here is where to stay in Athens.

Knossos palace on crete – an insta-worthy archaeological site .

It’s the best-preserved palace of the Minoan Civilization and home to the legend of King Minos, the Labyrinth, and the Minotaur, as well as the story of Daedalus and Icarus.

But the Minoans were more than just a collection of myths. They were a highly developed society, with advanced commercial routes in the Aegean and even established colonies. In the palace, you will be amazed at the urban planning skills of this civilization.

Choose to visit early in the day or late in the afternoon to enjoy the place with fewer crowds and more pleasant temperatures since the island is sweltering from April until October .

When visiting Heraklion, you can stay in a city center hotel like Galaxy Iraklio Hotel.

Island of Delos – Near Mykonos

The sacred island of Delos is one of the most fascinating archaeological sites you can choose to visit in Greece . A visit to the site can make an excellent day trip if you’re spending your holidays on the island of Mykonos.

Delos is a small islet a few miles from Mykonos and a UNESCO World Heritage Site . According to Greek mythology , the island was where the god of light, Apollo, and his twin sister Artemis were born.

A sacred place in ancient times, the most remarkable places to discover include the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, and the famous avenue of the lions. There’s also a small museum on the island with objects found in the place during the excavations.

Acrogiali Hotel, in the area of Platys Gialos and right on the beach, is a magnificent place to stay in Mykonos if you’re traveling with all the family.

The Sanctuary Of Delphi

Another superb archaeological site to visit in Greece is the magnificent site of Delphi , which is among the most important and most visited sites in Greece. Delphi was ancient Greece’s most important oracle, dating back to the 8th century BC.

In the past, people from the rest of the Mediterranean basin would come to the oracle of Delphi seeking advice from the priestesses.

Check the Temple of Apollo, the Treasury of the Athenians, the Theatre, the Stadium, and the Gymnasium in this Greek archaeological site. Don’t forget to check out the museum right next to the sanctuary.

Although a visit to Delphi can be a great day trip from Athens, many travelers prefer to take it easy and spend some time in the area of Delphi. Nidimos Hotel is located less than a kilometer from the archaeological site and has unpaired vistas from the surrounding landscape.

Ancient Olympia Peloponnese, Ancient Greek Ruins Not To Be Missed

One of the most critical sanctuaries in ancient Greek times, devoted to worshiping the most important of all Greek gods, Zeus, Olympia is located in the heart of the Peloponnese and is one of the Greek sites loved by children.

Also, the Olympic Games would take place in Ancient Olympia. The games were first held during the 7th century BC, and they were organized to honor the great Greek gods . Known to have been the most remarkable sports competition, even wars and battles would come to a stop for the Olympic Games to take place.

When you visit, don’t miss the temples of Zeus and Hera , the workshop of sculptor Phidias, and the area where the sports and games took place. The Museum of Olympia is another fantastic visit to add to your itinerary.

In the heart of Ancient Olympia, ideal for families with kids, Hotel Hercules combines a friendly atmosphere and great-value accommodation . If you prefer to rent a villa and explore the Peloponnese , check out the fantastic facilities of Bacchus, a traditional stone mansion with beautiful views of the surrounding area, just 3 kilometers away from Ancient Olympia.

Ancient Epidaurus

According to the myth, Epidaurus was where the god of healing, Asclepius, was born. Therefore, the area became an important healing center of antiquity. Also, in the area of Peloponnese , this religious center, which is vital for the sanctuary of Asclepius, is an important archaeological site in Greece that you can visit.

Essential festivals and festivities were held on the site to honor the god, especially in the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, which dates back to the 4th century BC. The construction is made of marble and stone and has stunning acoustics. Not far from Ancient Olympia, it’s a good idea to include both visits in your Peloponnese trip .

Check out the Amalia Olympia Hotel, which is a great location to visit Ancient Olympia and Epidaurus. Kids will love their fantastic swimming pool!

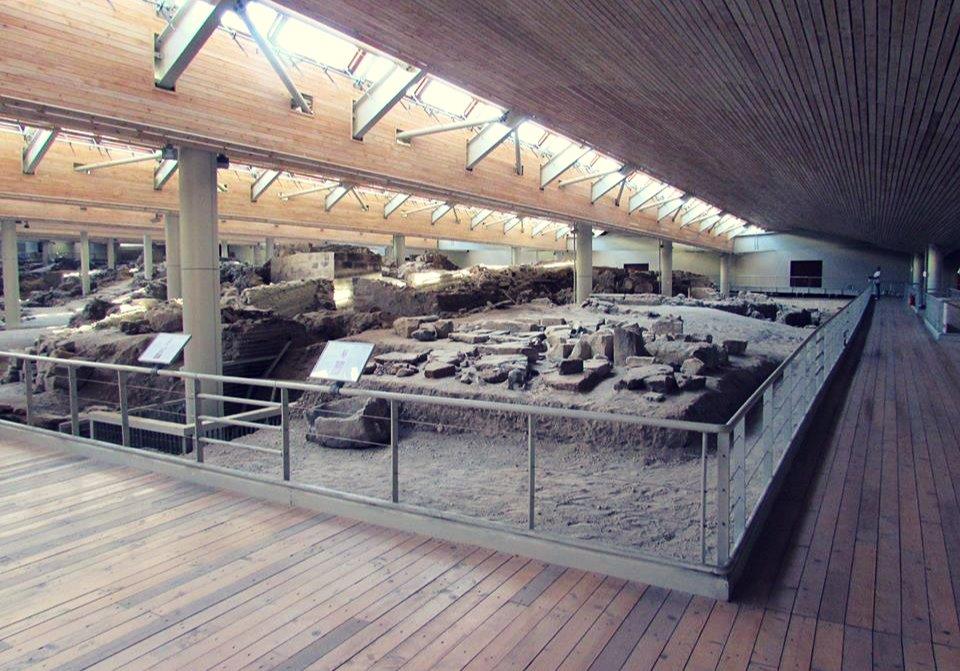

Akrotiri Excavations On Santorini

If you’re visiting Santorini this summer , don’t miss a trip to any of the island’s archaeological sites.

South of Santorini, you can discover the excavations of Akrotiri , one of the most important Aegean settlements that date back to the early Bronze Age. Kids are fascinated when visiting a site destroyed by the eruption of the Santorini volcano, which, however, helped preserve the ancient town of Akrotiri as the ashes of the eruption wrapped and preserved the site, which was discovered many years afterward.

Inside the site, it’s possible to observe the multi-storeyed houses with frescoes, the unique sewer system, stone streets (like the ones in the different settlements of modern Santorini), and endless storage vases and furniture.

On the island, it’s also possible to check Ancient Thera, a Dorian settlement located on top of the Mesa Vouno Mountain, in the central portion of the island. This ancient town is developed on a terraced territory and features antique buildings such as the Sanctuary of Artemis and the impressive Agora.

Staying in the Akrotiri area instead of choosing the overcrowded and more expensive Oia is a great idea to explore the lesser-known areas of Santorini , including Akrotiri. One of the best places to stay in the area is Kokkinos Villas, which has direct views of the famous Santorini caldera and the volcano.

To visit Ancient Thera, the location of Kamari is a great place to book accommodation. Check out the eco-friendly Boathouse Hotel, which is located right on the beach of Kamari and boasts an outdoor pool that kids really love!

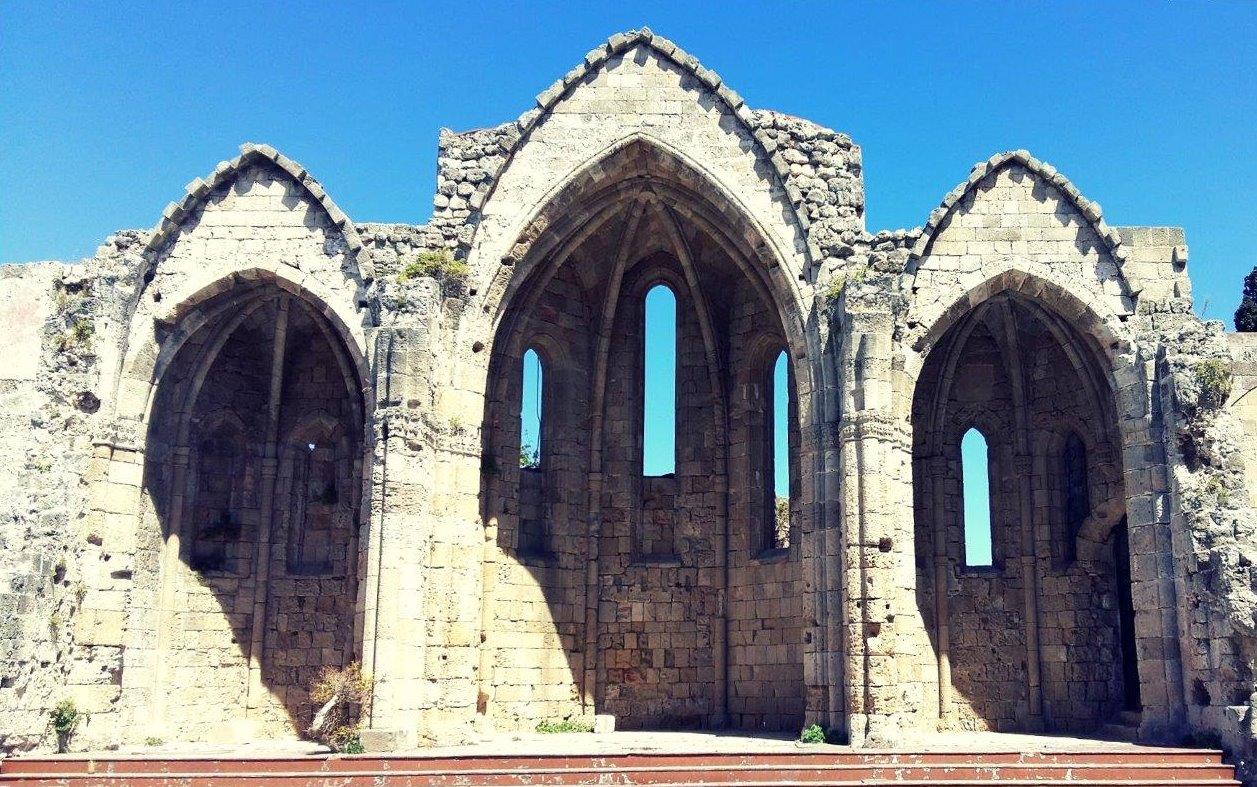

Medieval Town Of Rhodes

The fantastic medieval city of Rhodes is a great place to explore, which kids genuinely enjoy. Here, the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem left their traces on every angle of the island.

UNESCO declared the old Medieval town of the Knights of Rhodes a World Heritage site .

Kids enjoy the vistas of the most spectacular European castle, the cobbled streets, and the unique Gothic towers that populate the area.

Camelot Traditional and Classic Hotel is the perfect place to stay and surround yourself with the Medieval atmosphere of Rhodes. Located in the medieval town of Rhodes , the stone-built venue has a unique mosaic-tiled courtyard that the whole family can enjoy.

Brands We Use And Trust

Important ancient sites in greece that are easy to get to.

Meteora is not just an ancient site but a breathtaking landscape. The monasteries perched atop rock pillars are a sight to behold. It’s easily accessible by car or bus from Athens and offers a unique combination of natural beauty and historical monastic life that’s unlike anywhere else in the world.

Archaeological Site of Mycenae, Peloponnese

Mycenae, a key center of Greek civilization from the 15th to the 12th centuries BC, offers a rich history through its ruins, including the Lion Gate and the Royal Tombs. It’s relatively easy to reach from Athens by car or organized tours, making it a convenient day trip.

Situated in the heart of modern Athens, the Ancient Agora is not only easy to get to but also full of fascinating ruins and the well-preserved Temple of Hephaestus. It provides a glimpse into the civic, commercial, and social life of ancient Athens.

Archaeological Site of Philippi, Eastern Macedonia

Philippi is notable for its historical significance in ancient Macedonia and its role in early Christianity. It’s a bit farther afield but accessible by car or bus from Thessaloniki, offering insights into both Hellenistic and Christian periods through its ruins.

The Archaeological Site of Eleusis (Elefsina) – Located just 18 kilometers northwest of Athens, Eleusis is a site of immense ancient religious significance, known for the Eleusinian Mysteries. The site is easily accessible from Athens by public transport or car, and its fascinating history related to Demeter and Persephone is compelling for those interested in ancient myths and rites.

Recommended For History Buffs

For real history experts and well-traveled individuals looking for depth and unique insights into Greece’s ancient past, the following five sites offer profound historical significance and are a bit off the conventional path.

Archaeological Site of Aigai (Vergina)

The site of the ancient Macedonian kings’ royal palace and their tombs, including the tomb of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great. Aigai is a UNESCO World Heritage site, offering a deep dive into Macedonian culture and history. Its discovery has significantly contributed to our understanding of ancient Macedonian civilization.

The Ancient City Of Corinth

Located near the Isthmus of Corinth, the ancient city was a major player in ancient Greek and Roman times. Its complex history, involving commerce, politics, and religion, plus the well-preserved ruins like the Temple of Apollo and the Acrocorinth, make it fascinating for those with a deep interest in ancient civilizations.

The Royal Tombs At Vergina

While part of the larger Aigai site, the Royal Tombs deserve a separate mention for their extraordinary archaeological value and the stunning finds, including the tomb of Philip II. The site provides unparalleled insight into Macedonian burial practices and royal wealth.

For those deeply interested in ancient religious practices, Eleusis offers a profound look at the Eleusinian Mysteries, one of the most secretive and significant religious rites of ancient Greece. The site’s artifacts and ruins, including the Telesterion hall, provide a tangible connection to ancient Greek spiritual life.

Pythagoreion And Heraion of Samos

An ancient fortified port with Greek and Roman monuments and the nearby Heraion, sanctuary of the goddess Hera, on the island of Samos. This UNESCO World Heritage site encapsulates the scientific, architectural, and religious advancements of the ancient Greek world.

FAQs Greek Archaeological Sites

What are the most important archaeological sites in greece.

Greece is home to numerous significant archaeological sites. Some of the most important ones include the Acropolis, Delphi, Olympia, Epidaurus, Mycenae, Delos, Knossos, Akrotiri, Dion, and Dodona.

What can I see at the Acropolis in Athens?

The Acropolis of Athens is the most famous archaeological site in Greece. Here, you can explore iconic ancient structures like the Parthenon, the Temple of Athena Nike, the Erechtheion, and the Propylaia.

What is there to see in Delphi?

Delphi, an important oracle of ancient Greece, offers various archaeological treasures. Visit the Temple of Apollo, the ancient theater, the Terrace of the Lions, and the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

Where can I find the birthplace of the Olympic Games?

Ancient Olympia in southern Greece is a significant sanctuary dedicated to Zeus and renowned as the birthplace of the Olympic Games. Explore the ancient stadium, the Temple of Zeus, and the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

What makes Mycenae an important archaeological site?

Mycenae is one of the oldest ancient sites in Greece, showcasing the ruins of the Mycenaean civilization. Visit the famous Lion Gate, the beehive tombs, the royal tombs, and the Treasury of Atreus.

What can I discover at Knossos in Crete?

Knossos is the most important Minoan site, showcasing the ancient palace and urban planning of the Minoan civilization. Explore the ancient ruins, the frescoes, and the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion.

Are there any interesting archaeological sites in the Greek Islands?

Apart from Knossos, the Greek Islands offer many fascinating archaeological sites. Delos, a small islet near Mykonos , was a sacred and trade center and features notable monuments like the Temple of Apollo. Akrotiri in Santorini preserves an ancient Minoan settlement buried by a volcanic eruption.

What can I see in northern Greece?

Northern Greece is rich in history and features several important archaeological sites. Visit the city of Dion, an ancient Macedonian sanctuary, or explore the ancient ruins of Philippi and Vergina.

What are some other important archaeological sites in mainland Greece?

Aside from Athens, mainland Greece boasts many remarkable archaeological sites. Explore the ancient city of Corinth or visit Dodona with its oracle of Zeus and the impressive theater of Dodona.

What can I expect to find at Epidaurus?

Epidaurus is known as a religious center and healing sanctuary in ancient Greece. Don’t miss the ancient theater, famous for its remarkable acoustics, or explore the Sanctuary of Asklepios and the archaeological museum.

Move This Adventure To Your Inbox & Get An Instant Freebie

No spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

Basics For Any Visit To These Ancient Sites In Greece

While exploring ancient sites in Greece, we suggest you keep these tips in mind;

- Carry a small backpack containing water, sunscreen, a hat , and your camera. These four elements should always be with you when visiting Greek archaeological sites as they are generally in the open air, and there’s no way to be protected from the sun. Your skin will be thankful

- Double on sun protection if you visit with kids

- Choose comfy travel clothes , such as shorts and T-shirts (add a cover-up for your shoulders if you’re visiting a religious monument or a monastery). Choose light material that is breathable and allows freedom of movement

- Remember to add a light sweater if you also visit museums. Some of them have rooms that have their temperature adjusted to preserve the pieces showcased better, and in some cases, temperatures can vary a lot from one room to the other within the same museum

So, there you have it, a complete guide to Greece’s top archaeological sites. Which famous archaeological site will you visit this summer?

- How To Tip In Greece

- Car Rental And Driving Tips In Greece

- Where To Stay In Greece To Avoid the Crowds

- What To Expect & Do In September In Greece

- Things To Do In Greece During The Winter

- Packing Tips For Greece

- How To Order Coffee In Greece

- How To Get From Santorini To Crete

- Best Beach Resorts In Greece

- Most Beautiful Cities In Greece

- A Guide To Kos Island

- Fascinating Facts About Greece

Wonderful archaeological sites attraction in Greece. Greece is the country that I dreaming to go because of this history and ancient structural. Hope someday I’ll go there. Thanks for sharing and keep it up.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe To Unlock Your FREE Customizable Travel Packing List & All Our Best Tips!

Unlock Your FREE Customizable Travel Packing List!

Subscribe Now For Instant Access To Stress-Free Packing

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

How to get away from it all in Greece

Discover gods, heroes, and less visited villages in the Peloponnese.

This 13th-century fortress castle guards Methoni, a historic port on Greece’s Peloponnese peninsula.

Whether your tastes skew toward Homer or Hollywood (think of those sparring Spartans in 300 ), you’ve likely encountered the Peloponnese , the peninsula at the southernmost tip of Greece that was the heart of ancient Hellenic culture. A mythic land where gods and heroes walked, the Peloponnese still evokes epic qualities fit for laurels and lyrical poems. With a beguiling mix of classical ruins, wild landscapes, and some of the best culinary treasures the country has to offer, it’s an attractive alternative to well-trod tourist routes around Athens and the Greek islands.

Separated from mainland Greece by the Corinth canal, the Peloponnese has for centuries been a crossroads of the eastern Mediterranean, its landscape littered with the remains of ancient civilizations and would-be conquerors. Temples to the Greek gods still stand, as do palaces built by the powerful Spartan and Mycenaean empires, and fortresses that testify to the waves of invaders—Ottoman, Frank, Venetian—who across the centuries have staked their claim to the peninsula. ( Discover underrated Mediterranean destinations to visit now. )

The modern-day hordes are thankfully kept at bay—the Peloponnese has largely been spared the overdevelopment of Greek tourist traps such as Mykonos and Santorini. The lovely Arcadia region, lush with cypress, poplar, and olive groves, bears traces of the virgin wilderness where nymphs, naiads, and the horned god Pan once frolicked. Spend a few days hiking the Lousios Gorge and you’re less likely to encounter tourists than monks cloistered in the area’s working monasteries, some of which date to the Middle Ages. (Speaking of olive groves, here’s another sun-soaked Greek island where you can eat like a god .)

The remote Mani region, at the southern end of the peninsula, has in recent years been made easily accessible to travelers. Famed for the ferocity of its inhabitants, the region maintains a rough, austere beauty. With its dramatic mountain passes and sheer cliffs plunging straight into the sea, the Mani holds much of the wild allure that seduced Paris and Helen of Troy. According to Homer, the star-crossed lovers spent the first night of their elopement here—before their ill-fated affair sparked the Trojan War.

Costa Navarino is an upscale resort development with activites that include boating, biking, hiking, and kitesurfing.

The Bourtzi tower in the Castle of Methoni once served as a prison.

The Lousios Gorge is a popular hiking spot on the peninsula.

History has a powerful hold on the Peloponnese, but part of the region’s appeal is the way that the past merges with the present. Visit the ancient site of Olympia and you can crouch in the same starting blocks as the athletes who raced in the first Olympic Games. Nemea , where Hercules performed his first labor by slaying the lion that was terrorizing the city, is at the heart of one of the most important wine regions driving the Greek wine renaissance today. ( Visit the all-marble stadium that hosted the first modern Olympics. )

In Epidaurus , the majestic fourth-century theater isn’t just a throwback to the days of Aeschylus and Euripides: it’s the focal point for one of the highlights of the Greek cultural calendar, an annual arts festival (May to October) during which thousands pack into the amphitheater for performances. Ringed by hills and hidden by forests, the ancient site was excavated little more than a century ago—a hint, perhaps, of other undiscovered treasures awaiting Peloponnesian travelers.

The hill town of Dhimitsana, in the Arcadia region of the Peloponnese, perches above the Lousios River.

- Nat Geo Expeditions

Become a subscriber and support our award-winning editorial features, videos, photography, and more—for as little as $2/mo.

Related Topics

- FOOD TOURISM

You May Also Like

How to spend the perfect food weekend on the Greek island of Tinos

This Greek island offers all the splendor of Santorini without the crowds

The 31 best Greek islands to visit in 2024

Welcome to Hydra, the Greek island that said no thanks to cars

How to explore Grenada, from rum distilleries to rainforests

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

29 Travel and Travel Writing

Maria Pretzler is Lecturer in Ancient History at Swansea University.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Greek travellers tried to take their city with them: travel is typically conducted as a civic act, one justified and defined by one's tie to the city: trade, for example, or martial aggression, or colonization. This article discusses the range of travel experiences reflected in surviving literature. The study of ancient travel focuses on the process of travelling, on individual travellers' movements and their reactions to particular journeys and places. The evidence is therefore mainly literary, with valuable additions from epigraphic sources. The remains of sites that were particularly attractive to ancient travellers, depictions of their means of transport, shipwrecks, and traces of ancient roads can add further information. Greek travel literature had a strong influence on early modern geography and ethnography, and it still has an impact on how people understand the Greek world.

G reeks liked to think about their world by tracing colonists' movements from the old motherland to distant Mediterranean shores: they considered mobility as a crucial factor in defining what, and who, was essentially Greek. Myth and epic poetry set the scene by depicting an earlier age of travellers, be it the Achaeans on their overseas campaign against Troy and then on their tortuous journeys to return home, or adventurous heroes such as Heracles or Jason and the many founders of Greek cities everywhere. For us, the Odyssey in particular provides a wide range of responses to the experience of travelling overseas in the crucial period when Greek colonization began to shape the ancient Mediterranean as we know it. In Odysseus' tales we encounter a variety of travellers engaged in friendships, diplomacy, and marriage outside their own community, and many people risking adventures for gain through trade, piracy, war, or increased knowledge. Others were forced to leave their home, either displaced as slaves or seeking refuge after conflict. Odysseus, always longing to go home to Ithaca while experiencing both the benefits and the horrors of a long overseas journey, shows how the image of the traveller could be reconciled with that other crucial aspect of Greek identity, a close and lasting connection to one's polis. Many did, however, not return home: by the end of the archaic period we find hundreds of colonies, new poleis, around the coasts of the Mediterranean, and some Greeks sought opportunities well beyond the regions settled by colonists.

It is possible to document complex and dense connections between places and regions around the ancient Mediterranean and beyond (Horden and Purcell 2000 ), but most of the evidence for high levels of connectivity in the ancient world does not provide information about the actual process of travelling. The general and vague information derived from imported objects found on archaeological sites suggests the movements of people without offering much insight into the mode or direction of particular journeys. Nevertheless, the general observation that travel was not an exceptional activity in the ancient world should inform our approach to ancient texts dealing with travel experiences. The study of ancient travel focuses on the process of travelling, on individual travellers' movements and their reactions to particular journeys and places. The evidence is therefore mainly literary, with valuable additions from epigraphic sources. The remains of sites which were particularly attractive to ancient travellers, depictions of their means of transport, shipwrecks, and traces of ancient roads can add further information.

Much of what we know about ancient travel concerns the small, eloquent elite that generally dominated the ancient literary record. Throughout antiquity travel was a part of life for wealthy individuals who were involved in the affairs of their community. They were particularly active in maintaining contacts beyond their community, from the elaborate guest-friendships of the Homeric epics to embassies to the emperor in the Roman period. Throughout antiquity, members of the elite relied on widespread contacts which could include acquaintances who were not Greek. Travelling as we see it in most ancient texts was expensive, because eminent people travelled in grand style, with numerous attendants and considerable luggage (Casson 1994 : 176–8). Early Christian texts, particularly the Gospels, Acts, and some of St Paul's epistles, look beyond the small, wealthy elite and offer a different cultural perspective, but this valuable source-material has yet to be fully integrated with classical scholarship.

Information about the activities and routines of ancient travel has to be pieced together from disparate references in ancient texts, and the bulk of the evidence dates from the Roman period (Casson 1974 ; Camassa and Fasce 1991 ; André and Baslez 1993 ). The preferred mode of long-distance travel was by ship: not only was sea travel faster and more comfortable (e.g. Pliny, Epistles 10.17a; Casson 1974 : 67–8, 178–82), but few important Greek sites were located far from the sea. Journeys on land probably often meant walking, even for long distances, although wealthy travellers would use carriages. Mainland Greece at least had a dense road network suitable for vehicles which reached even remote, mountainous locations. Many of these roads date back to the archaic or early classical period and they were in use until the end of antiquity (Pikoulas 2007 ; Pritchett 1980 : 143–96). These practical aspects of ancient travel are rarely the focus of modern research, but they are crucial for our understanding of how ancient travellers interpreted their surroundings. The slow pace of ancient journeys facilitated intensive encounters with landscapes, sites, and local people, while ancient travellers were often less interested in the wider context of their location. Geographical overviews and accurate maps of large regions seem to have remained the domain of scholarly experts, while many travellers may have adopted a view which organizes the landscape along particular routes without paying much attention to a ‘global’ perspective (cf. the Peutinger Table and Pausanias, with Snodgrass 1987 : 81–6).

Trade, war, and the search for opportunities may have accounted for a majority of individual journeys in antiquity (Purcell 1996 ), but these activities are rarely at the centre of attention. Journeys made for the sake of travelling, usually for the spiritual and intellectual benefit of a particular individual, account for much of the information about travel experiences that can be found in ancient texts, and modern scholarship reflects this emphasis on what we might call ‘cultural travel’. Early Greek travellers were often engaged in new discoveries, encountering unknown regions and strange cultures. The exploration by Greeks of regions around the western Mediterranean and the Black Sea may be reflected in the epic tradition, particularly the Odyssey , although it came too early to leave credible traces in the literary record. Areas beyond the Mediterranean remained largely unknown well into the Hellenistic period. The Atlantic coasts of both Europe and Africa were occasionally visited by explorers who recorded their observations, for example Hanno and Pytheas of Massalia (Carpenter 1966 ). Egypt and the Middle East had always been more accessible to the Greeks, not least because there they encountered highly developed cultures that were much older than their own.

By the end of the archaic period Greeks had travelled widely and extended the boundaries of their known world: from Egypt they had reached the upper Nile Valley and brought news of regions further south, and, from the sixth century, knowledge about distant regions of the East as far as India could be obtained through good connections with the Persians. Herodotus criticizes the theories about the shape of the earth inferred from such information by the geographical theorists of sixth-century Ionia, but he also testifies to the usefulness of maps created in this period and he includes geographical information about distant regions in his own work (Herodotus 4.39, 5.49; Harrison 2007 ). Alexander's conquests in the East and the expansion of the Roman empire, especially in western Europe, provided the Greeks with opportunities to reach hitherto unknown regions and to obtain more detailed geographical information (Polybius 3.59; Clarke 1999 ). The edges of the earth, however, remained a matter of legends about unusual peoples and cultures and wondrous natural phenomena (Hartog 1988 : 12–33; Romm 1992 ). All surviving ancient explorers' tales have been subjected to intense scrutiny to match them to actual regions and cultures. Recent scholarly attention, however, has been focused on the particularly Greek perspective on alien cultures which often describes strange people in terms of stark contrasts with what was familiar to the writer and his audience. In fact, authors dealing with ‘barbarians’ often seem more concerned with exploring their own culture than with giving an accurate picture of a distant region and its people. (Hartog 1988 : 212–59).

Most ancient travellers stayed within the familiar confines of the Mediterranean, but there was plenty of scope for ‘cultural’ travel in the Greek world and among its immediate neighbours. Educated Greeks would embark on sightseeing tours to visit famous places, for example a number of historical sites in mainland Greece, including Athens, Olympia, Delphi, and perhaps Sparta, some of the cultural centres of Asia Minor such as Ephesus or Pergamon, and Ilium as the main location of the Trojan War. Egypt, with its spectacular ancient sites (Casson 1974 : 253–61), was also an attractive destination. These sightseeing activities are sometimes described as ancient tourism, but this term is rather misleading because it invites analogies with the seasonal mass movements of today. The Grand Tours of wealthy Europeans of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would be a more appropriate analogy (see Cohen 1992 ). Most visitors were particularly interested in ancient monuments with historical connections, artworks by famous artists, and sights that could be classified as curiosities. In most places with important historical monuments a visitor could employ professional tourist-guides to explain the sights, and wealthy travellers could apparently rely on members of the local elite to provide a tour appropriate for refined tastes and educated interests (as Plutarch does in his work On the Pythia's Prophecies ; and cf. Jones 2001 ).

In recent years ancient pilgrimage has attracted particular interest (Hunt 1984 ; Dillon 1997 ; Elsner 1997 ; Elsner and Rutherford 2005 : esp. 1–30). The applicability of this term to the activities of ancient travellers is contentious (Morinis 1992 : 1–28; Scullion 2005 : 121–30), but valuable interpretations of ancient texts have emerged from this line of enquiry. Throughout antiquity many sanctuaries saw large numbers of visitors, and some festivals could attract considerable crowds. Many people undertook such visits on their own initiative, but states also maintained regular official links with specific sanctuaries beyond their borders. The concept of pilgrimage invites new enquiries into the function and meaning of such journeys, especially as a means of defining identities and collective memories. Pilgrimage can also be a useful category in assessing ancient attitudes to historical sites. After all, the classical texts played a dominant role in the lives of educated Greeks and determined their approach to places that were in some way linked to the literary tradition. Historical sites, such as important battle-fields or places that played a crucial role in the Homeric epics, allowed visitors to explore localities with which they were intimately familiar from their reading since childhood, and which were part of a common Greek consciousness. Visits to such places could therefore have a profound effect which cannot easily be distinguished from a spiritual or religious experience (Hunt 1984 ). This approach to spiritual, cultural, and emotional aspects of pagan visits to significant places also allows a new evaluation of Christian pilgrimage in late antiquity (e.g. Egeria), by considering it in the context of earlier, pre-Christian traditions (Hunt 1982 ; Holum 1990 ).

Travelling was seen as an important source of knowledge and wisdom, and it was closely linked to the ideals of Greek culture and education ( paideia ) (Pretzler 2007 b ). A traveller could learn by seeing and experiencing different places and civilizations for himself, and he might gain access to information which was not available in Greece. The Greeks were aware that some civilizations were far more ancient than their own, and they assumed that in some countries, for example Egypt, Mesopotamia, or India, travellers might be able to acquire considerable knowledge, particularly about the remote past. There were many legends about the extensive journeys of famous sages such as Solon or Pythagoras, echoed by later traditions about the adventures of Apollonius of Tyana, or Dio Chrysostom's claims about his own wanderings while he was in exile (Hartog 2001 : 5, 90–1, 108–16, 199–209). In the Roman period, many aspiring young men from all over the Roman world travelled to acquire a Greek education: they would move to one of the leading cultural centres such as Pergamon, Athens, or Smyrna to study with a distinguished sophist. Prominent intellectuals could enhance their reputation by travelling to give lecture tours and to compete with their peers (Anderson 1993 : 2–30). Educated Greeks were therefore expected to be acquainted with famous cities and sites, and such personal knowledge influenced intellectual debates and texts. Experience gained through travelling became particularly important to enhance the credibility of arguments and reports. Authors often stress that they have personally seen places or witnessed events they are describing, and such claims of autopsia became a standard literary topos, particularly in historical and geographical works (e.g. Thucydides 1.1; Strabo 2.5.11; Polybius 3.4; Nenci 1953 ; Lanzillotta 1988 ; Jacob 1991 : 91–4).

While travelling and travel experiences play a crucial role in many ancient texts, there is no clearly defined genre of Greek travel literature. Modern examples of the genre often offer an insight into personal experiences on a journey, and they reflect reactions to strange landscapes, places, and people (Campbell 2002 ). Few ancient texts cover any of these aspects extensively, and a study of literary responses to travel experiences needs to include texts which touch upon the subject although they belong to different genres. There is no comprehensive modern study of Greek travel writing, and the re-evaluation of relevant texts as travel literature is a relatively recent phenomenon (e.g. Elsner 2001 ; Hutton 2005 ; Roy 2007 ); much work remains to be done in this field. As far as we can tell, the expectations of ancient readers of travel texts differed considerably from those of their modern counterparts. Few ancient writers provide a clear sense of the topography of a place, and they rarely attempt to create a comprehensive image of a location that would allow readers to visualize what the traveller has seen. In fact, ancient travel writers are usually very selective about what to report: particular features of a landscape are usually only mentioned if they represent a curiosity or if they are relevant to the author's aims, for example sporadic topographical details in a historian's account of a battle. Detailed descriptions of objects were the subject of rhetorical exercises ( ekphrasis ), and landscape descriptions play a particular role in pastoral poetry, but they rarely take up much space in ancient travel accounts (Bartsch 1989 : 7–10; Pretzler 2007 a : 57–63, 105–17).

Ancient travel writing (in the widest sense) can be roughly divided into two categories: on the one hand there are accounts of particular journeys, and on the other hard there are texts which present facts about places or cultures without discussing the process of travelling. The tradition of such ‘factual’ geographical texts was traced back to the ‘Catalogue of Ships’ in the Iliad (2.484–760; cf. 2.815–77), which provides a list of Greek cities and tribes in a roughly geographical order. The earliest geographical texts probably took the form of periploi (e.g. ps. -Scylax), essentially seafarers' logs describing coastlines with important places and landmarks, or stadiasmoi which listed paces and distances along overland routes (Giesinger 1937 ; Janni 1984 : 120–30). Hecataeus' Periodos Gēs developed this genre further by combining a periplous -style description of the world with a scientific discussion of the shape of the earth and the layout of the continents. Later geographers continued to rely on verbal descriptions of coastlines and regional topographies which were never fully superseded by maps (Janni 1984 : 15–19; Jacob 1991 : 35–63). As Strabo shows, geographical works could include information about the landscape, history, and culture of particular places. Texts dealing with particular regions, for example local histories (e.g. Atthidography, Arrian's Bithyniaca ), could go into more detail and would usually rely on an intimate knowledge of landscape, monuments, and local traditions.

Most descriptions of regions and sites were probably mainly interested in historical monuments, religious sites, and significant artworks, not unlike the ‘cultural’ travel-guides of today (Bischoff 1937 ; Hutton 2005 : 247–63). Only two such works survive, Lucian's On the Syrian Goddess , a description of the sanctuary of Atargatis in Hierapolis which is clearly not meant entirely seriously (Lightfoot 2003 ), and Pausanias' Periēgēsis Hellados , ten books describing the Peloponnese and a part of central Greece which represent the longest extant ancient travel text (Habicht 1985 ; Alcock, Elsner, and Cherry 2001 ; Hutton 2005 ; Pretzler 2007 a ). Pausanias, a Greek from Asia Minor carried out extensive research between about 160 and 180 ce , but he rarely refers to his own travel experiences, probably in order to maintain his credibility as an objective observer. Pausanias shows little interest in the life of contemporary communities or the natural landscape. Instead, he focuses on sites with a historical or religious significance, and he provides detailed information about the symbolic and cultural interpretations that Greeks could attach to the landscape. The Periēgēsis follows a long ethnographic tradition, and particularly Herodotus, but instead of reflecting on his own identity by contrasting it with the strange customs of barbarians, Pausanias applies his observations to the heartlands of the Greek world, and he presents an intensive study of the history and state of Greek culture in his own time. A fragment of an early Hellenistic description of Greece by Heraclides Criticus offers a very different view of the landscape of Attica and Boeotia (Pfister 1951 ; Arenz 2006 ). He adopts an often humorous and somewhat flippant tone to comment on the customs and character of contemporary people and on general conditions for a traveller. Heraclides also records his impressions of the landscape and the general appearance of the cities on his route: his approach to the landscape remains unique among the preserved ancient Greek travel texts.

It seems that authors who described places without discussing a particular journey found it easier to assert their credibility. Accounts of individual journeys had a long tradition, but such stories rarely allowed clear distinctions between fact and fiction. Heated discussions about the veracity of tales about distant regions show that ancient readers were aware of this problem, but their conclusions about particular texts often do not agree with modern opinions (e.g. Strabo 1.2.2–19; Romm 1992 : 184–93; Prontera 1993 ). Fictional travel accounts should therefore be included in any study of ancient travel literature because they add to the range of possible literary responses to travel experiences, even if they may not provide factual information about ‘real’ places or journeys. Greek travel writing begins with a fictional tale, namely the Odyssey , with its stories about monsters and incredible events (Jacob 1991 : 24–30; Hartog 2001 ). What is more, its main narrator, Odysseus, is clearly an unreliable reporter who tells untrue stories (‘Cretan tales’) about himself and his adventures, and the epic demonstrates how a traveller can construct false tales which will stand up to scrutiny. Odysseus therefore was a hard act to follow: in his wake no traveller reporting adventures in distant lands could be without suspicion, and many did indeed feel free to add fantastic details to their accounts. The earliest explorers' accounts usually took the form of a periplous which would include some details about specific adventures and discoveries (e.g. Hanno, Pytheas of Massalia). In the Roman period, Arrian revisited the genre and demonstrated its potential complexities: he reports his activities as governor of Cappadocia in a Periplous of the Black Sea , which also allows him to explore his own position as a Greek with multiple identities (Stadter 1980 : 32–41; Hutton 2005 : 266–71; Pretzler 2007 b : 135–6).

Few ancient travel accounts deal with emotional responses to a journey or the transforming impact of the experience on an individual's character, knowledge, or spiritual state. Aristides' Sacred Tales are unique in presenting the authors' personal perspective on his activities, including many journeys, in the pursuit of health and a special relationship with Asclepius (Behr 1968 : 116–28). Most texts dealing with such personal experiences are fictional, and can take the form of extensive accounts, for examples a trip to India in Philostratus' Life of Apollonius , or the Greek novels that usually send their main characters on convoluted journeys before they can settle down to live happily ever after (Morgan 2007 ; Rohde 1960 : 178–310). Some travel authors make no attempt to disguise the fact that their stories are invented, and this can lead to fresh perspectives on the experience of travel. For example, Apuleius' Golden Ass (cf. Lucian, Ass ) takes the opportunity to consider a journey from the point of view of a beast of burden, and it describes a spiritual transformation which turns the main character into a devout follower of Isis. The story also provides a rare chance to observe various travellers who are not members of the elite (Schlam 1992 ; Millar 1981 ). Lucian's fantastic stories ( Lovers of Lies, True Histories ) and other examples of ancient fiction can be seen as a humorous exploration of the many devices employed by travel writers to make their accounts believable (Ní Mheallaigh 2008 ).

Travel accounts could recover some credibility in the context of historiography: after all, Herodotus' Enquiries ( Historiai ) involved extensive travelling around the eastern Mediterranean, and autopsy remained crucial to enhance a historian's authority. Some journeys were themselves historical events, for example long military campaigns, and they inspired a new kind of travel account which owed much to historiography but could also follow some of the conventions of ancient adventurers' tales. Xenophon's Anabasis is the most extensive personal account of a specific journey that survives from antiquity, although the author never admits that he is in fact one of the main characters in the story. Xenophon includes specific information about distances, topography, flora, fauna, and local people, and he gives the impression that decades after the events he can draw on detailed memories, perhaps even a travelogue (Cawkwell 2004 ; Roy 2007 ). His perspective, however, is not that of an explorer whose main aim it is to describe a foreign region, but that of a historian who includes details about landscape and people when they are relevant to the events described. Alexander's conquests inspired a number of participants to write accounts which probably took the form of historical accounts in the mould of Xenophon's Anabasis (Pearson 1960 ). In the East, Alexander's military operations turned into a journey of exploration, and his scientific staff gathered reliable, factual information about areas which had hitherto been almost unknown to the Greeks (Strabo 1.2.1; 2.1.6). Well-founded knowledge could, however, be superseded by fantasy: if Strabo (2.1.9) is anything to go by, realistic reports about India did not have a lasting impact and were soon replaced by the old traditions about an exotic land full of strange wonders (Seel 1961 ; Romm 1992 : 94–109). Alexander's campaign became itself the subject of the Alexander Romance , which reinterpreted historical events in the tradition of myths and fictional adventure stories: in ancient travel writing, imagination could sometimes be stronger than reality.

Like Odysseus, Greek travellers are often unreliable witnesses of places and events they have seen, but their tales offer great insights into ancient perceptions of the world. Greek travel literature had a strong influence on early modern geography and ethnography, and it still has an impact on how we understand the Greek world. Since the Renaissance, western travellers who set out to discover the eastern Mediterranean relied on ancient texts to guide them to classical sites and to help them interpret the historical landscape. They also drew on similarities between the reactions of travellers in the Roman period and their own feelings about ancient sites and the loss of Greek culture. Ultimately, our understanding of antiquity owes much to ancient travellers who contributed their observations and interpretations to the definition of Greek culture and identity. The reception of ancient travel literature, especially of major texts such as Strabo or Pausanias, deserves attention, not least in the context of the development of our own disciplines, namely Classics, Ancient History, and Classical Archaeology.

Suggested Reading

The classic account of many facets of ancient travel in English is Casson (1994) . Casson gathers the ancient evidence to describe the activities and aims of ancient travellers, and his work offers a useful introduction to the subject. André and Baslez (1993) cover similar ground, but in addition to gathering and digesting the sources their work also reflects more recent developments in the study of ancient travel, and they offer more discussion of the cultural and intellectual context of their material. Two collections of articles on travel and travel writing, namely Camassa and Fasce (1991) and Adams and Roy (2007) , provide a good insight into a variety of lines of enquiry that have influenced the study of ancient travel in recent years.

Ancient travel writing has mainly been covered in works about specific authors. Recently the study of Pausanias in particular has led to further investigations of travel and travel writing. Pretzler (2007 a ) offers a general discussion of ancient travel, travel literature, and attitudes to geography and landscapes. Hutton (2005) analyses methods of travel writing, with a particular emphasis on the geographical structure of texts that deal with landscapes. Alcock, Cherry, and Elsner (2001) presents a wide range of approaches, including a number of papers discussing the reception of Pausanias.

Travel to distant places and the role the edges of the known world played in the imagination has been at the centre of stimulating discussion in recent years. Carpenter (1966) provides a basic overview of ancient explorers and their discoveries on the margins of the oikoumenē . Ideas about distant regions are discussed in Romm (1992) , and Hartog (1988 and 2001 ) contributes many valuable insights. Pilgrimage is another special aspect of travelling that has recently attracted a good deal of scholarly attention: much progress has been made in the analysis of pilgrimage in an ancient pagan as well as an early Christian context. Elsner and Rutherford (2005) is a collection of conference papers which offer a good overview of recent debates.

A dams , C. and R oy , J. eds. 2007 . Travel, Geography and Culture in Ancient Greece, Egypt and the Near East . London.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

A lcock , S. E., C herry , J. F., and Elsner, J. eds. 2001 . Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece . Oxford.

A nderson , G. 1993 . The Second Sophistic: A Cultural Phenomenon in the Roman Empire . London.

A ndré , J.-M. and Baslez, M.-F. 1993 . Voyager dans l'antiquité . Paris.

A renz , A. 2006 . Herakleides Kritikos ‘Über die Städte in Hellas’. Eine Periegese Griechenlands am Vorabend des Chremonideischen Krieges . Munich.

B artsch , S. 1989 . Decoding the Ancient Novel: The Reader and the Role of Description in Heliodorus and Achilles Tatius . Princeton.

B ehr , C. A. 1968 . Aelius Aristides and the Sacred Tales . Amsterdam.