An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Trade and Geography in the Spread of Islam *

Stelios michalopoulos.

† Brown University, Department of Economics, 64 Waterman st., Robinson Hall, Providence, RI 02912, USA, CEPR, and NBER, ude.nworb@olahcims .

Alireza Naghavi

‡ University of Bologna. Department of Economics, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy, [email protected]

Giovanni Prarolo

§ University of Bologna. Department of Economics, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy, [email protected] .

Associated Data

In this study we explore the historical determinants of contemporary Muslim representation. Motivated by a plethora of case studies and historical accounts among Islamicists stressing the role of trade for the adoption of Islam, we construct detailed data on pre-Islamic trade routes, harbors, and ports to determine the empirical regularity of this argument. Our analysis – conducted across countries and across ethnic groups within countries – establishes that proximity to the pre-600 CE trade network is a robust predictor of today’s Muslim adherence in the Old World. We also show that Islam spread successfully in regions that are ecologically similar to the birthplace of the religion, the Arabian Peninsula. Namely, territories characterized by a large share of arid and semiarid regions dotted with few pockets of fertile land are more likely to host Muslim communities. We discuss the various mechanisms that may give rise to the observed pattern.

“ O you who believe! Eat not up your property among yourselves unjustly except it be a trade amongst you, by mutual consent. And do not kill yourselves (nor kill one another). Surely, Allah is Most Merciful to you.” The Noble Qur’an (Hilali-Khan translation), Surah An-Nisa’, 4:29 1

1. Introduction

Religion is significantly correlated with a range of economie and politicai outcomes both within and across countries. 2 This can, perhaps, be linked to the fact that religious people tend to be more trusting in general ( Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales, 2003 ). Given the importance of religion in society, a natural question to ask is what factors contributed to the distribution of religions around the globe that we see today.

In this study, we focus on the spread of one religion – Islam. There has been growing interest in Muslim societies in recent years amongst economists and political scientists, see for example, Blydes (2014) , Campante and Yanagizawa-Drott (2015) , Clingingsmith, Khwaja, and Kremer (2009) , Jha (2013) , and Kuran (2004) . Our analysis investigates the role that ancient trade routes have played in facilitating the spread of Islam. Motivated by numerous case studies on the historical relationship between trade and Islam, we construct detailed data on pre-Islamic trade routes, ports, and harbors. Proximity to the pre-600 CE trade network is a robust predictor of today’s Muslim adherence in the Old World. We also show that Islam spread successfully in regions that are ecologically similar to the birthplace of the religion, the Arabian Peninsula.

The empirical analysis establishes that countries located closer to historical trade routes are more likely to be Muslim. We then investigate whether this empirical regularity holds at the more disaggregated level of ethnic homelands within countries. Exploiting within-country variation has straightforward advantages. First, it allows us to test in a sharper manner whether differences in proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes are meaningful predictors of local adherence to Islam. Second, leveraging within contemporary-state variation in Muslim representation mitigates concerns related to the endogeneity of current political boundaries. Modern states, arguably, have affected religious affiliation in a multitude of ways including state-sponsored religion. As such, it is crucial to account for these nationwide histories.

These findings are in line with a rich body of earlier work by prominent Islamicists including Lapidus (2002) , Berkey (2003) , and Lewis (1993) , who have extensively discussed the role of long-distance trade, noting both the diffusion of Muslims along trade routes ( Geertz, 1968 ; Lewis, 1980 ; Trimingham, 1962 ) and the importance that Islamic scriptures confer on trade-related matters ( Cohen, 1971 ; Hiskett, 1984 ; Last, 1979 ). An innovation of Islam was the practice of direct trade, where Muslim merchants personally carried goods over long distances along the trade routes rather than relying on intermediaries. For example, the acceptance of Islam in most of Inner Asia, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa is known to have occurred primarily through contacts with Muslim merchants ( Insoll, 2003 ; Lapidus, 2002 ; Levtzion, 1979 ). In addition, the highly personal practice of exchange created preference for Muslims to conduct trade with co-religionists (Chaudhuri, 1995; Kuran and Lustig, 2012 ). Therefore, merchants converting to Islam enjoyed substantial externalities like access to the Muslim trade network, steady trade flows, and a reduction in transaction costs. In Section 2 we provide a brief overview illustrating the role of trade in the Islamization process in various parts of the Old World.

Although the primary contribution of this study is to establish how proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes has influenced the distribution of Muslim communities in the Old World, we also explore whether the ecological similarity to the Arabian peninsula of a given region predicts the presence of Muslim communities. But which are the salient geographic features of the cradle of Islam? The Arabian peninsula has a distinct geography, mainly consisting of desert and semi-arid landscapes with a few regions of moderate fertility such as today’s Yemen and other scattered oases in the interior. On the eve of Islam, frankincense, myrrh, vine, dyes, and dates were produced in these fertile pockets ( Ibrahim, 1990 ). To capture this distinct landscape, we construct for each country/ethnic homeland the Gini coefficient of land suitability for agriculture and show that ecological similarity to the Arabian Peninsula (reflected in the degree of inequality in the potential for farming across regions) increases Muslim representation.

We discuss various explanations consistent with this less-well-known fact and show that groups residing along geographically unequal territories have a particular production structure (both historically and today) with pasture dominating the semi-arid landscape and farming taking place in the few relatively fertile regions. These differences in the underlying productive endowments may generate gains from specialization and provide a basis for trade as a means of subsistence. This is indeed the case for a cross-section of ethnographic societies we examine. So, to the extent that trade is likely to flourish when the parties involved adhere to a common code of exchange, the trade-promoting institutional framework of Islam would find likely converts across such territories.

A complementary interpretation links geographic inequality to social inequality and predation and echoes Ibn Khaldun (1377) , one of the greatest philosophers of the Muslim world, who observed that a crucial factor for understanding Muslim history is the central social conflict between the primitive Bedouin and the urban society (“town” versus “desert”). The argument is that long-distance trade opportunities confer differential gains to populations residing in the relatively more fertile regions, fostering predatory behavior from the poorly endowed ones. Along the same lines, contemporary scholars have noted that when farmers and herders coexisted in absence of an institutional framework coordinating their activities, their interactions were often conflictual, disrupting trade flows across these territories ( Richerson, 1996 ). We conjecture that Islam with its redistributive economic principles was a unifying force aimed at reining in the underlying inequality in exchange for security for the trading caravans ( Michalopoulos, Naghavi, and Prarolo, 2016 ). The premise that geographie inequality becomes more salient when long-distance trade opportunities arise generates an auxiliary prediction. Namely, the intensity of adoption of Islam across unequally endowed regions should increase with proximity to trade routes. This prediction is borne out in the data.

Our study belongs to a wider literature in economics that explores the interplay between the economic and political environment and (religious) beliefs and rules. Contributions include works by Greif (1994) , Benabou and Tirole (2001) , Botticini and Eckstein (2005 , 2007 ), Cervellati and Sunde (2017) , Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (2016) , Platteau (2008 , 2011 ), Rubin (2009) , Becker and Woessmann (2009) , and Greif and Tabellini (2010) . Moreover, by focusing on the spread of a particular religion, our work is closely related to that of Cantoni (2012) who explores how proximity to Wittemberg, the birthplace of Martin Luther, influenced the diffusion of Protestantism. The evidence provided on the consistent geographic pattern followed by the Muslim world also makes contact with the studies by Engerman and Sokoloff (1997 , 2002 ) and Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2001 , 2002 ), among others, that stress the role of geography in shaping institutional outcomes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we provide a historical narrative of the significance of trade for the spread of Islam. In Section 3 , we discuss the data and present the empirical analysis conducted across countries and ethnic groups. In Section 4 , we dig deeper into what distance to trade routes and geographic inequality reflect and outline possible explanations consistent with the uncovered evidence. Section 5 summarizes and discusses avenues for future research.

2. The Spread of Islam along Historical Trade Routes

Islam has spread at a breathless pace since the time of Muhammad. Nevertheless, the mode of expansion has differed across time and space ranging from conquests, to trade, to proselytization and migrations. During the early phase, Islam expanded mainly through conquests within a certain radius around Mecca. The initial military conquests, even if they did not entail forced conversion, eventually resulted in Muslim-majority populations occupying large swaths of land. These areas overlap with contemporary countries close to Mecca including the entire Arab World in the Middle East and North Africa, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and slightly further away in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The territories featured important trade hubs during the pre-Islamic era, particularly those along the Silk Road in Asia and the Red Sea in North Africa. Most of these lands were part of the Persian Empire, which was the largest and most important empire of the time to be conquered and concede to Islam. Famous trade hubs along the routes of the Persian Empire were Rey (in Iran), Samarkand and Bukhara (in Uzbekistan), and Merv (in Turkmenistan).

The process of Islamization farther away from the birthplace of Islam was intimately linked to trade. The Islamic world came to dominate the network of the most lucrative international trade routes that connected Asia to Europe (and by sea to North Africa). With full Muslim control of the western half of the Silk Road by mid-8th century, any long-distance exchange had to traverse Muslim lands, giving trade a central role in the further propagation of the religion. Muslim merchants carried the message of Islam wherever they traveled. This was possible because of the Muslim practise of “direct” trade, one of the most remarkable innovations of Islam. Prior to Muslim conquests, trade was conducted by a network of local merchants who traded exclusively in their homelands. In other words, they played the role of intermediary agents with goods (often spices) being transported from one carrier to another by short journeys, creating a trade-relay. Muslims instead did not rely on intermediaries and personally travelled the entire length of the journey, crucial for the diffusion of the religion along the trade routes and at the destination. The spread of Islam was hence greatly enhanced by social contact as a consequence of trade ( Miller, 1969 ; Wood, 2003 ).

On the receiving end, the new religion appealed to the local merchants because it legitimized their economic base more than most belief systems present at that time. Merchants converting to Islam had clear advantages including (i) cooperation within the Muslim trading network, (ii) valuable contacts to expand their trade, and (iii) rules governing commercial activities naturally favoring Muslims over non-Muslims ( Sinor, 1990 ; Foltz, 1999 ).

Proselytization was a third factor that inffuenced the spread of Islam across locations most distant to Mecca. Trade routes were also important in this process as the charismatic Sufi preachers travelled along these routes to perform missionary activities. Finally, migration of Muslims (again through trade routes) and their inter-marriages at the destination also contributed to the spread of Islam along the trade routes distant from Mecca.

2.1. The Adoption of Islam by Ethnie Groups in the Vicinity of Trade Routes

The historical accounts linking trade routes and Muslim adherence across countries are indicative of their importance for the spread of Islam. Nevertheless, given the power of the state to inffuence its religious composition, one may wonder whether a similar nexus between proximity to trade hubs and Muslim representation exists within countries that are not religiously homogeneous. In what follows, we review the historical record on the emergence of Islam for specific countries with varying religious diversity including China, Tanzania, Mali (the location of the former Ghana Empire), Indonesia, and India. A systematic empirical analysis at the ethnic group level for each of these countries is relegated to Section 3.3 .

Figures 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, and 1e provide snapshots of pre-Islamic trade routes along with contemporary Muslim representation for groups located in these five regions making apparent the link between the two (see Section 3.1 below for a description of the underlying data).

Figure 1 portrays Muslim adherence at the ethnic group level and historical trade routes within five countries (1a: China, 1b: Mali, 1c: Tanzania, 1d: Indonesia and 1e: India). Muslim adherence is represented in quintiles at the level of ethnic group, where actual homelands are from the Ethnologue version 15 and data on religious affiliation from the World Religion Database. Darker shades represent higher Muslim shares in the population. In Figures 1a, 1c, and 1e the trade routes are depicted as thick, black-and-white dashed lines and correspond to pre-600 CE. These routes are digitized from Brice and Kennedy (2001) . The ancient ports and harbors, depicted as circled stars, are from Arthur de Graauw (2014) . In figure 1b trade routes are relative to 900 AD, while in figures 1c and 1d ports in year 600 CE (1800 CE) are represented with circled stars (circled dots). Country borders are represented with a thin dashed grey line.

2.2. Inner Asia

By the 8th century, Islam was no longer the religion of only the Arab world and had expanded geographical borders along the Silk Road. Conversions were often a result of economic considerations and the financial benefits afforded to those joining the Ummah. Even among the conquered people in Central Asia, Islam continued to gain a hearing without coercion as merchants spread the religion. Muslim traders traveled as far as the capital of the Tang dynasty, Chang’an, in the Chinese Empire. The 9th century saw the rise of Islamic kingdoms in Central Asia, especially the Samanid Empire, the first Persian dynasty after the Arab conquests. The Islamization of the nomadic Turkic peoples of Central and Inner Asia occurred during the 10th century along the trade routes. This process has been linked mainly to their participation in the oasis-based Silk Road trade and was accelerated by the conversion and the expansion of three Turkic Muslim dynasties of the Karakhanids, the Ghaznavids, and the Seljuks ( Meri and Bacharach, 2006 ).

The major ethnic groups close to trade routes with a substantial Muslim representation in this region are the Uyghurs, the Hui, the Kazakhs, the Kyrgyz, and the Tajiks. These ethnic groups also exist within China today and comprise the Muslim minority in the country. They are all located around Xianjiang, a vast region of deserts and mountains along the Silk Road in Northwest China.

The Uyghurs are one of the largest ethnic groups in Inner Asia, and their Islamization dates back to the Karakhanids in early 10th century, the first Turkic dynasty to convert to the new religion. The core of the Uyghurs’ homeland was Kashgar, an oasis city located in the West of China near the current-day border of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, which historically served as a strategic trade hub between China, the Middle East, and Europe ( Roemer, 2000 ). The Hui people are another Muslim Chinese minority historically connected to Muslim merchants travelling along the Silk Road. Besides Xianjiang, they also live farther east in Central China. A cluster of this group can be found today in Xi’an, where they form the majority of a large Muslim community (the dark spot in the center of China in Figure 1a ). Xi’an was the first city in China where Islam was introduced. ( Soucek, 2000 ). The longest segment of the Silk Road runs across the Central Asia and Kazakhstan. The religion practiced by the majority of Kazakhs is Islam since its introduction in the region by the Arabs during the 9th century. The Kyrgyz tribes also adopted Islam as Muslim traders and then Sufi missionaries began to move out from scattered towns to the nomadic steppes, spreading Islam among the tribal groups. They are known to have adopted Islam between the 8th and 12th centuries. The Tajiks on the other hand, started converting to Islam in the late 11th century ( Minahan, 2014 ).

2.3. East and West Africa

Islam spread through the well-established trade routes of the east coast of Africa via merchants. The earliest records for trade in East Africa indicate Greco-Roman trade down the Red Sea and along the Somali coast to the Tanzanian coast. This was followed by the trade of frankincense, myrrh, and spices with the Persian Gulf from the 2nd to the 5th century CE. Soon Zanzibar Island also became a trade hub and remained so until the 9th century CE, when Bantu traders settled on the Kenyan-Tanzanian coast and joined the Indian Ocean trade networks interacting with the Somali and Arab proselytizers. Shanga, an early Swahili town on Pate Island in the Lamu Archipelago, is a good example of early influence through Muslim traders as they built the first small wooden mosque in the region around 850 CE ( Shillington, 2005 ). Islam was established on the Southeast coast soon after, and eventually a full-scale prosperous Muslim dynasty known for trading gold and slaves was established at Kilwa on the coast of modern Tanzania. By the 11th century CE, several settlements down the east coast were equipped with mosques, and Islam emerged as a unifying force on the coast to form a distinct Swahili identity ( Trimingham, 1964 ).

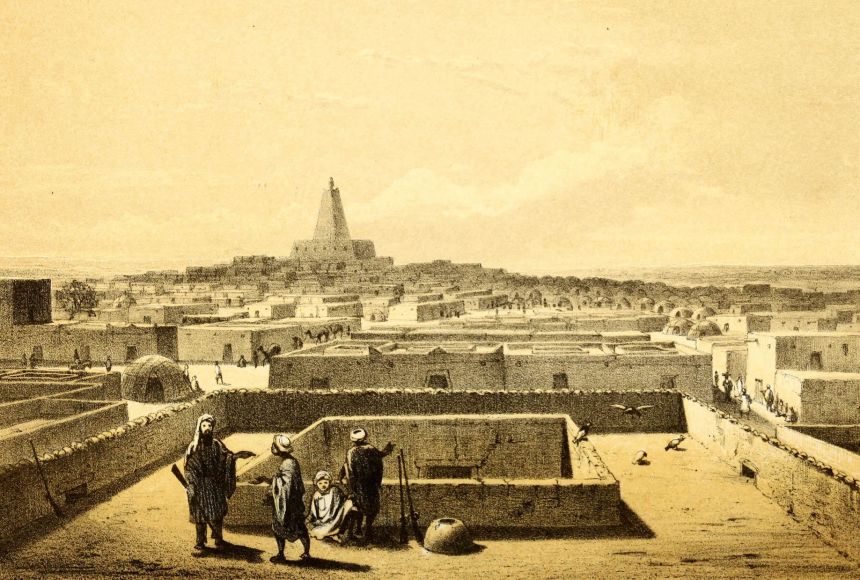

Historical accounts suggest that the early penetration of Islam was even more effective along the caravan routes of West Africa. Trans-Saharan trade started on a regular basis during the 4th century and presents a clear example of subsistence from trade between the people of the Sahara, forest, Sahel, and savanna ( Boahen, Ajayi, and Tidy, 1966 ). While present since 500 CE, the significance of the trans-Saharan trade routes rose and declined over time depending on the empire in power and the security that could be maintained along the routes ( Devisse, 1988 ). Islam was introduced through Muslim traders along several major trade routes that connected Africa below the Sahara with the Mediterranean Middle East, such as Sijilmasa to Awdaghust and Ghadames to Gao. Muslims crossed the Sahara into West Africa trading salt, horses, dates, and camels for gold, timber, and foodstuff from the ancient Ghana empire. The trade-friendly elements of Islam, such as credit or contract law, together with the information networks it helped create, facilitated long-distance trade. By the 10th century, merchants to the south of the trade routes had converted to Islam. In the 11th century CE the rulers began to convert. The first Muslim ruler in the region was the king of Gao, around the year 1000 CE. The Kanem empire (the Kanuri people), located at the southern end of the trans-Saharan trade route between Tripoli and the region of Lake Chad, followed after being exposed to Islam through North African traders, Berbers, and Arabs ( Trimingham, 1962 ; Levtzion and Pouwels, 2000 ; Robinson, 2004 ).

2.4. South and Southeast Asia

There is ample historical evidence indicating that Arabs and Muslims interacted with India from the very early days of Islam, although trade relations had existed since ancient times. Malabar and Kochi were two important princely states on the western coast of India where Arabs and Persians found fertile ground for their trade activities. The trade on the Malabar coast prospered due to the local production of pepper and other spices. Islam was first introduced to India by the newly converted Arab traders reaching the western coast of India (Malabar and the Konkan-Gujarat region) during the 7th century CE ( Elliot and Dowson, 1867 ; Makhdum, 2006 ; Rawlinson, 2003 ).

Cheraman Juma Masjid in Kerala is thought to be the first mosque in India. It was built towards the end of Muhammad’s lifetime during the reign of the last ruler of the Chera dynasty, who converted to Islam and facilitated the proliferation of Islam in Malabar. The 8th century CE marked the start of a period of expansion of Muslim commerce along all major routes in the Indian Ocean, suggesting that the Islamic influence during this period was essentially one of commercial nature. Initially settling in Konkan and Gujarat, the Persians and Arabs extended their trading bases and settlements to southern India and Sri Lanka by the 8th century CE, and to the Coromandel coast in the 9th century CE. These ports helped develop maritime trade links between the Middle East and Southeast Asia during the 10th century CE ( Wink, 1990 ).

The people of the Malay world have been active participants in trade and maritime activities for over a thousand years. Their settlements along major rivers and coastal areas were important means of contact with traders from the rest of the world. The strategic location of the Malay Archipelago at the crossroad between the Indian Ocean and East Asia, and in the middle of the China-India trade route, aided the rapid development of trade in the region ( Wade, 2009 ). In particular, the Srivijaya kingdom (7th −13th century CE) on the straits of Malacca attracted ships from China, India, and Arabia plying the China-India trade routes by ensuring safe passage through the Straits of Malacca ( Andaya and Andaya, 1982 ).

Similar to those in Africa, rulers in Southeast Asia often converted to Islam through the influence of Muslim merchants who set up or conducted business there. While the landed Hindu-Buddhists were content to let the trade come to them, the Muslim merchants, lacking a fixed land base, made their profits from trade at the location of exchange. Consequently, the people of Southeast Asia began to accept Islam and create Muslim towns and kingdoms. By the late 13th century CE, the kingdom of Pasai in northern Sumatra had converted to Islam. At the same time, the collapse of Srivijayan power at the end of the 13th century CE drew foreign traders to the harbors on the northern Sumatran shores of the Bay of Bengal, safe from the pirate lairs at the southern end of the Strait of Malacca ( Houben, 2003 ; Ricklefs, 1991 ). Around 1400 CE, a new kingdom was established in Malacca (on the north shore of the Malacca Strait). The rulers of Malacca soon accepted Islam in order to attract Muslim and Javanese traders to their port by providing a common culture and offering legal security under Islamic law ( Holt, Lambton, and Lewis, 1970 ; Esposito, 1999 ). Finally, the Bugis, an ethnic group along Java’s northern coast adopted Islam later in the 16th century CE when Muslim proselytizers from West Sumatra came in contact with the people of this region who conducted trade ( Mattulada, 1983 ).

3. Empirical section

3.1. the data sources.

The historical overview vividly illustrates the importance of pre-existing trade routes for the diffusion of Islam but also suggests the beneficial impact of Islam on the further expansion of the trade network. To make sure we capture the first part of this two-way relationship, we construct our main explanatory variable by measuring the distance between the relevant unit of analysis (a country or an ethnic homeland) and the closest historical trade route or port before 600 CE, reflecting the structure of trade flows already present in the Old World in the eve of Islam. 3

The location of trade routes is outlined in Brice and Kennedy (2001) whereas the location of ancient ports and harbors is taken from the work of De Graauw, Maione-Downing, and McCormick (2014) who collected and identified their precise locations. The result is an impressive list of approximately 2, 900 ancient ports and harbors mentioned in the writings of 66 ancient authors and a few modern authors, including the Barrington Atlas. We complement the pre-600 CE routes mapped in Brice and Kennedy (2001) with information on the Roman roads identified in the Barrington Atlas ( McCormick, et al., 2013 ). Finally, we also extend the trade network up to 1800 CE, digitizing the relevant information from Brice and Kennedy (2001) , and supplementing it with routes within Europe, Southeast Asia, West Africa, and China mapped in O’Brien (1999) during the same time period. We expect these data to be useful to other researchers. See Figures 2a and 2b for the reconstruction of the pre-Islamic and pre-1800 CE trade network, respectively.

Figure 2a (2b) shows the Old World network of Roman roads (from the Barrington Atlas), ancient ports and harbours (from Arthur de Graauw, 2014 ) and trade routes (from Brice and Kennedy, 2001 ) in 600 AD (1800 AD).

In the cross-country analysis, the dependent variable employed is the fraction of Muslims in the population as early as 1900 CE reported by Barrett, Kurian, and Johnson (2001) . For the ethnic group analysis, the dependent variable is the fraction of Muslims and of other religious denominations in 2005 from the World Religion Database (WRD). 4 These estimates are extracted from the World Christian Database and are subsequently adjusted based on three sources of religious affiliation: census data, demographic and health surveys, and population survey data. 5 In absence of historical estimates of Muslim representation at an ethnic group level, we are constrained in using contemporary data. Reassuringly, country-level Muslim representation derived from the group-specific estimates of the WRD are highly correlated (0.93) with the respective country statistics on Muslim adherence in 1900 CE.

Information on the location of ethnic groups’ homelands is available from the World Language Mapping System (WLMS) database. This dataset maps the locations of the language groups covered in the 15th edition of the Ethnologue (2005) database. The location of each ethnic group is identified by a polygon. Each of these polygons delineates the traditional homeland of an ethnic group; populations away from their homelands (e.g., in cities, refugee populations, etc.) are not mapped. Also, the WLMS (2006) does not attempt to map immigrant languages. Finally, ethnic groups of unknown location, widespread ethnicities (i.e., groups whose boundaries coincide with a country’ boundaries) and extinct languages are not mapped and, thus, not considered in the empirical analysis. The matching between the WLMS (2006) and the WRD is done using the unique Ethnologue identifier for each ethnic group within a country. 6

To capture how similar the ecology of a given region is to that of the Arabian Peninsula, we construct the distribution of land quality and, in turn, the Gini coefficient of regional land potential for agriculture across countries and homelands. Under the assumption that land quality dictates the productive capabilities of a given region, populations on fertile areas would engage in farming whereas pastoralism would be the norm in poorly endowed regions (see more on this in Section 4 ). In the absence of historical data on land quality, we use contemporary disaggregated data on the suitability of land for agriculture to proxy for regional productive endowments. The global data on current land quality for agriculture were assembled by Ramankutty et al. (2002) to investigate the effect of future climate change on contemporary agricultural suitability and have been used extensively in the recent literature in historical comparative development. Each observation takes a value between 0 and 1 and represents the probability that a particular grid cell may be cultivated. 7

Finally, we combine anthropological information on ethnic groups from Murdock (1967) with the Ethnologue (2005) , enabling us to examine the pre-colonial societal and economic traits of Muslim groups. We discuss these two datasets in more detail as we introduce them to our analysis.

3.2. Cross-Country Analysis

We start by investigating the relationship between distance to trade routes in the Old World and Muslim adherence across modern-day countries. The cross-country summary statistics and the corresponding correlation matrix of the variables of interest are reported in Appendix Table 1 .

To estimate how proximity to trade routes shapes Muslim adherence we adopt the following OLS specification:

where % Muslim 1900 i is the fraction of the population in country i adhering to Islam in 1900 CE. 8

In Column 1 of Table 1 , we report the univariate relationship between distance from trade routes and Muslim adherence. The coefficient is economically and statistically significant. Across modern-day countries variation in the distance to pre-Islamic trade routes accounts for roughly 9% of the observed variation in Muslim representation. The magnitude of the estimated coefficient, moreover, suggests that a country located 1, 000 kilometers farther from the 600 CE trade routes has 15% lower Muslim representation. Naturally, one may wonder whether this association remains robust to other possible determinants of Muslim adherence that may be correlated to distance to trade routes. In Column 2, we add a series of distance terms that may be potential confounders. The literature reviewed in Section 2 unequivocally suggests that proximity to Mecca is likely to be a strong predictor for the spread of Islam, and this is indeed what we find. The precisely estimated coefficient on distance to Mecca suggests that countries that are 1, 000 kilometers closer to Mecca see a 7% increase in their Muslim share, and countries further away from the equator are less likely to be Muslim. Distance to the coast by itself does not significantly affect Muslim representation. These three additional location attributes significantly increase the predictive power of the empirical model, the R 2 jumps to 23%; nevertheless, the coefficient of interest only slightly declines and remains precisely estimated.

Table 1 reports OLS estimates associating the share of Muslims with geographical variables. Observations are at the level of countries, the sample is the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa). In all specifications the dependent variable is the share of Muslims in 1900 from McCleary and Barro (2005). All specifications include the constant (not reported) and column (5) includes a set of continental effects.

The Supplementary Appendix gives detailed definitions, data sources and summary statistics for all variables. Standard errors in parentheses are robust to heteroskedasticity. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

In the rest of the Columns of Table 1 , we add additional geographic variables. The goal is twofold. First, to make sure that the uncovered relationship between distance to trade routes and Muslim adherence is not driven by some other geographic factor, and second, and perhaps more importantly, in doing so, we attempt to shed light on the geographie covariates of Islam. Given the recent interest among growth economists on the environmental determinants of comparative development, the list of potential geographic candidates is long. So, our choice of variables is disciplined in the following manner. Since we are interested in exploring whether a given region’s ecological similarity to the Arabian peninsula predicts the presence of Muslim communities, we construct the Gini coefficient of land suitability for agriculture using the data from Ramankutty et al. (2002) .

The following example may help illustrate the type of geographies that this measure reflects. Uzbekistan and Poland are both equally close to pre-Islamic trade routes (approximately 190 kilometers) but have very different ecologies. On the one hand, less than 10% of Uzbekistan’s territory lies in river valleys and oases that serve as cultivable land, whereas the rest of the country is dominated by the Kyzyl Kum desert and mountains. In our data, the Gini coefficient of land quality is estimated to be 0.59 (82nd percentile) with an average land quality of 0.25. On the other hand, Poland has a much more homogeneous geography in terms of farming potential with a Gini coefficient of 0.16 (30th percentile) and an average land suitability of 0.56. As of 1900 CE, Uzbekistan was 98% Muslim whereas there were no Muslims in Poland. These stark geographic differences across Muslim and non-Muslim countries are readily visible in the our sample. Out of the 127 countries in the Old World, those 35 (92) that have a Muslim absolute majority (minority) have median land quality equal to 0.22 (0.50) and median Gini coefficient in land quality of 0.54 (0.20). In Column 4 of Table 1 , we add both of these geographic indexes in logs to our benchmark specification. The estimated coefficient on proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes remains qualitatively and quantitatively intact. Moreover, the estimates suggest that low land suitability for agriculture and high inequality in the spatial distribution of this scarce factor are strongly predictive of the presence of Muslims across countries. Adding these two features in the regression increases the R 2 by 25 percentage points revealing the importance of geographic features in the spread of Islam. One may naturally wonder what potential mechanisms are behind this strong associations. We will return to this question in Section 4 .

In the rest of the columns in Table 1 , we check the robustness of our findings. Specifically, in Column 4, we add four more geographic traits. The log area of each country, the log of terrain ruggedness, an indicator reflecting the presence of a desert, and an indicator reflecting whether a country has any irrigation potential. 9 These geographic variables are chosen for the following reasons. First, Bulliet (1975) observed that Arab armies had a comparative advantage over desert terrain. In our sample of 127 countries, 38 feature some desert. Moreover, Bentzen, Kaarsen, and Wingender (2016) show that Muslim countries have higher irrigation potential and the latter may be correlated both with proximity to trade routes and inequality in the spatial distribution of land quality across cells within a country. Finally, ruggedness is controlled for as it is likely that more rugged countries limit the ability of foreign powers to penetrate them, and it also seems plausible that ruggedness is associated with the quality of land and trade routes ( Chaney and Hornbeck, 2016 ). Adding these controls neither changes the magnitude nor the precision of the estimates of our main explanatory variables. Among these new covariates, the only consistent predictor of Muslim representation is the potential for irrigation in line with Bentzen, Kaarsen, and Wingender (2016) . Finally, in Column 5 we add continental fixed effects to account for the broad geographic and historical differences between the continental masses finding similar results. Figure 3 plots non-parametrically the relationship between Muslim representation and distance to the pre-Islamic trade network after partialling out the covariates included in Column 5. 10

3.3. Cross-Ethnic-Group Analysis

The evidence so far reveals a strong cross-country association between Muslim representation and proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes as well as an unequal distribution of land endowments. However, the spread of Islam is a historical process that predated the emergence of modern nation states. Moreover, the historical record is replete with examples of current countries actively influencing their religious composition by promoting or demoting specific religious identities. Would the cross-country patterns survive if we were to account for the idiosyncratic historical legacies of contemporary states? To answer this we look at the religious affiliations of ethnic groups within countries. This allows us to control for country-specific constants and thus produce reliable estimates of the impact of trade routes on Muslim adherence.

In Appendix Table 2 Panel A, we report the summary statistics of the main variables employed in the cross-ethnic-group analysis. 11 An average ethnic group in the Old World has 21% of its population adhering to Islam in 2005, is 5, 230 kilometers from Mecca, and 1, 345 kilometers from trade routes before 600 CE. Appendix Table 2 Panel B shows the raw correlations among the main variables of interest. Ethnic-specific Muslim representation is negatively related to distance to Mecca (−0.24) and distance to trade routes in 600 CE (−0.22).

We adopt the following specification:

where δ c represents the country-specific fixed effects. 12

Before showing the results for all groups across the Old World, and motivated by the historical accounts summarized in Section 2 , in Table 2 we report bivariate regressions linking distance to pre-600 CE trade routes to contemporary Muslim adherence across linguistic groups within specific countries. In Columns 1, 2, and 3, we look at the religious composition of language groups in China, Mali (the location of the ancient Ghana empire), and Tanzania, respectively. Within each of these countries with varied historical legacies, and as foreshadowed by our early discussion, proximity to trade routes is a systematic predictor of Muslim communities. In Column 4, we focus on Indonesia, the country with the largest Muslim population worldwide. Across the 615 linguistic groups mapped by the Ethnologue, variation in the proximity of these homelands to pre-Islamic trade routes accounts for almost a quarter (22%) of the observed variation in contemporary Muslim adherence. In Column 5 we show that a similar pattern holds for India, a country where although Muslims are a minority they nevertheless represent the third-largest Muslim population across countries. In what follows, instead of showing country-specific estimates we use the entire sample of linguistic groups across the Old World to assess this link.

Table 2 reports OLS estimates associating the share of Muslims with distance from trade routes in 600AD in selected countries, at the level of ethnic group. In all specifications the dependent variable is the share of Muslims in 2005 at ethnic group level from the World Religion Database. All specifications include a constant (not reported).

To facilitate comparison across the different levels of analysis, the layout of Table 3A mimics that of Table 1 . The pattern found in the cross-country analysis resurfaces in the cross-ethnicity sample. The difference between Columns 1 and 2 in Table 3A is that in the latter we include country-specific constants. By doing so, the coefficient on the proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes increases considerably. Within modern-day countries, ethnic groups whose historical homelands are closer to the trade routes before 600 CE experience a significant boost in their Muslim representation. Namely, a 1, 000-kilometer increase in the former decreases Muslim representation by 17 percentage points. Columns 3 to 5 confirm the pattern obtained in Columns 2 to 4 of Table 1 . Regions closer to pre-Islamic trade routes, characterized by overall low land quality interspersed with pockets of fertile land are more likely to be populated by Muslim communities today. One noteworthy difference between the two levels of aggregation is that in the cross-group sample proximity to Mecca is now a reliable and precisely estimated correlate of Muslim adherence. In Figure 4 , we graph non-parametrically the association between Muslim representation across groups and distance to the pre-Islamic routes after partialling out all covariates included in Column 5 of Table 3A .

Table 3A reports OLS estimates associating the share of Muslims with geographical variables. Observations are at the level of ethnic group, the sample is the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa). In all specifications the dependent variable is the share of Muslims in 2005 from World Religion Database. Column (1) includes the constant (not reported), while the remaining columns include a set of country fixed effects.

The Supplementary Appendix gives detailed definitions, data sources and summary statistics for all variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the country level. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Groups of people coming under the direct rule of a Muslim empire might face incentives for converting to Islam related to social mobility ( Bulliet, 1979 ), a career within a Muslim bureaucracy ( Eaton, 1996 ), or lower tax rates (Chaney, 2008). For example, the lower tax rates granted to Muslims over non-Muslims within Muslim Empires or the status achieved by switching to the ruler’s religion might differentially affect conversion rates. Likewise, instances of forced conversion, religious persecution during the Muslim expansion, or Arab migration movements within the Muslim empires might have shaped the observed religious affiliation. Hence, in Columns 1 and 2 of Table 3B , we divide the ethnic groups based on whether they have been within a Muslim empire as classified by Iyigun (2010) . An ethnic group is considered to be outside a Muslim empire if the country to which it belongs today has never been part of a Muslim empire. Both the negative relationship of Muslim adherence and distance to trade routes and the positive link with geographic inequality remain significant outside the former Muslim empires.

Table 3B reports OLS estimates associating the share of Muslims with geographical variables. Observations are at the level of ethnic group, the samples are partitions of the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa). In Column 1 (2) the sample includes ethnic groups within (outside) the Muslim empires as classified by Iyigun (2010). In Column 3 (4) the sample is restricted to ethnic groups outside the Muslim empires where the dominant religion during the expansion of Islam was a non-monotheistic (monotheistic) one. In all specifications the dependent variable is the share of Muslims in 2005 from the World Religion Database.

It is clear that Europe traded with the Muslim world for centuries without large-scale conversions, indicating that there may be other factors at play than just access to the Islamic trade networks. Considering that monotheism was an attractive ideology compared to polytheism, regions outside the Muslim empires where monotheism was already present should be less receptive to the spread of Islam along trade routes. To explore this prediction, in Columns 3 and 4 of Table 3B , we focus on ethnic groups outside Muslim empires, further distinguishing between regions that were already monotheistic by 1050 CE as classified by O’Brien (1999) . Column 3 shows that limiting the sample to polytheistic areas during the diffusion of Islam, distance to trade routes is more precisely estimated. On the contrary, in Column 4 among the 172 groups where Christianity and Judaism were present by 1050 CE, proximity to trade routes negatively impacts Muslim representation suggesting that regions where monotheism was already in place found adherence to the Islamic institutional complex and access to the Muslim trade networks less beneficial.

The findings in Table 3B also raise the question whether the link between trade and religious adherence is particular to Islam. We tackle this issue by asking whether the identified relationship between Muslim representation and distance to trade routes systematically holds for other major religions. To facilitate comparisons in Column 1 of Table 4 , we replicate Column 5 of Table 3A where the dependent variable is the fraction of Muslims. In Columns 2, 3, and 4, we use as a dependent variable the percentage of people within an ethnic group adhering to three other major religions i.e., Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism, respectively. Lastly in Column 5, we use the fraction of the population adhering to local animistic, or shamanistic religions, known as Ethnoreligionists. The spatial distribution of these other religions does not seem to be influenced by the ancient trade routes. If anything Christians seem to be located further away from the pre-Islamic routes, a pattern mainly driven by groups in Asia and Africa.

Table 4 reports OLS estimates associating the share of different religions with geographical variables. Observations are at the level of ethnic group, the sample is the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa). In all specifications the dependent variable is the share of the population belonging to a given religion in 2005 measured at ethnic group level from the World Religion Database. All columns include a set of country fixed effects.

These findings highlight the, until now, neglected crucial role of trade in shaping the differential adherence to Islam across ethnic groups and shed new light on the geographical origins and spatial distribution of Muslims within modern-day countries.

Robustness Checks

In the Appendix , we offer a series of sensitivity checks for the main pattern established in Tables Tables1 1 and and3A. 3A . First, in Columns 1 and 4 of Appendix Table 3 , we replicate the specifications reported in Columns 5 of Tables Tables1 1 and and3A 3A with the difference being that we replace the dependent variable with a dummy equal to one for countries/groups where Muslims are the absolute majority. The estimated coefficients suggest that a 1, 000-kilometer increase in the distance to pre-Islamic trade routes decreases the probability of finding a country (group within a country) with a Muslim majority by 16% (12%). Second, in Columns 2 and 5, we explore the non-linearity of proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes to capture the plausibly diminishing role of distance for regions further away from the trade hubs. The quadratic term on distance to pre-600 CE trade routes alternates in sign across levels of aggregation and is highly insignificant. This can be rationalized in different ways. First, this pattern may reflect the fact that despite our efforts to collect a comprehensive set of indicators regarding the presence of pre-Islamic regional trade opportunities (manifested in routes, roads, and ports) we are fully aware that measurement error in the mapping of ancient routes is non-trivial.

Second, an alternative interpretation of the non-significance of the quadratic term is that Muslims starting from the pre-600 CE trade network and continuing over the next 1, 000 years until the beginning of the European colonialism significantly expanded trade routes, adding myriad new connections and reaching vast areas in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. This implies that the network relevant for discerning a diminishing role of the proximity to trade routes on the spread of Islam is not the pre-600 CE one but the routes on the eve of the colonial era. To explore the empirical validity of this conjecture, we expanded our trade-routes dataset with information up to 1800 CE. Columns 3 and 6 of Appendix Table 3 clearly show that Muslim representation both across countries and across-groups within countries has a concave relationship with proximity to trade. Further increasing distance to pre-industrial trade hubs for regions already far from them has little bearing on their Muslim adherence. A note of caution is in order. Using data on trade routes after 600 CE implies that the empirical relationship cannot be unequivocally interpreted as it clearly reflects a two-way interplay from initial trade routes to the spread of Islam and from the latter to the further development of the trade network.

4. Mechanisms

So far, we have established a strong positive association between proximity to ancient trade routes and contemporary Muslim adherence and a positive link between geographically unequal regions and the presence of Muslim communities. In this section, we do two things. First, we investigate whether a group’s proximity to trade routes predicts its reliance on trade. Second, we open the black box of what inequality in land quality reflects, using contemporary data on land use and historical data on the subsistence pattern across groups.

Historical Trade Routes and Historical Dependence on Trade

Is it the case that groups closer to trade routes are more likely to engage in trade? Historical data on dependence on trade are notoriously difficult to come by. To the best of our knowledge, the only dataset that records the extent of trade at the group level in the pre-industrial era is the Standard Cross Cultural Sample (SCCS), which reports detailed information for 186 historical societies worldwide. 13 The entry we are interested in is the share of the overall subsistence needs that comes from trade ( v 819). Across the 121 societies in the Old World we compute the distance from their centroids (reported in the SCCS) to the closest trade routes before 600 CE and in 1800 CE.

In Table 5 , we report the results. The coefficient estimate on distance to the pre-600 CE trade routes is negative but statistically insignificant. The absence of significance is easy to understand. All but four of the SCCS societies were recorded by ethnographers after 1750 CE, which implies that their effective exposure to trade was that of the trade network as of 1800 and not the one of 600 CE. Indeed, when we replace the distance to 600 CE trade routes with the one of 1800 CE, a strong negative relationship emerges. Groups closer to the 1800 CE trade network consistently derive a larger share of subsistence from trade. Examples include the Javanese in Indonesia and the Rwala Bedouin, a large Arab tribe of northern Arabia and the Syrian Desert. Both groups are a mere 70 kilometers away from the trade routes and ports in 1800 CE and derived as much as 25% of their subsistence from trade. In Column 3, we drop the four SCCS societies that were documented by ethnographers before 1750, namely the Babylonians, the Hebrews, the Khmer, and the Romans, finding a similar pattern.

What Does Land Inequality Capture?

Our motivation for constructing the inequality in the distribution of agricultural potential across regions is that this statistic reflects the ecological conditions of the Arabian peninsula, the birthplace of Islam. Indeed, across the 36, 582 land quality observations in the Old World among the 1, 285 cells that belong to the Arabian Peninsula, the Gini coefficient of land quality is 0.87 with an average land quality of 0.03 whereas the statistics for the rest of the regions are 0.57 and 0.32, respectively. 14 In a stage of development when land quality dictates the productive structure of the economy, one would expect societies along unequally endowed territories to have a specific productive structure with herding dominating the arid and semi-arid regions and farming taking place in the few fertile ones. This was certainly the economic landscape of the pre-industrial Arabian peninsula. Below, we verify this link using historical and contemporary data across groups on the dependence on pastoralism and agriculture.

The data on land use come from Ramankutty et al. (2008) and provide at the grid level of 0.083 by 0.083 decimal degrees estimates on the share of land allocated to pasture and agriculture in 2000. We aggregate this information at the homeland level to obtain a measure of how tilted land allocation is towards pasture. The data on the historical traits across groups come from Murdock (1967) who produced an Ethnographic Atlas (published in twenty-nine installments in the anthropological journal Ethnology) that coded around 60 variables, capturing cultural, societal, and economic characteristics of 1, 270 ethnicities around the world. We linked Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas groups to the Ethnologue’s linguistic homelands in the Old World. These two datasets do not always use the same name to identify a group. Utilizing several sources and the updated version of Murdock’s Atlas produced by Gray (1999) , we were able to identify the pre-colonial traits as recorded in the Ethnographic Atlas for 1, 210 linguistic homelands in the Ethnologue (2005) . 15

In the first three columns of Table 6 , the dependent variable is the log ratio of pastoral over agricultural area in 2000 across linguistic homelands. 16 All columns include country-specific constants. Within countries, groups residing along poor and unequally endowed regions display a larger land allocation towards animal husbandry compared to farming. Adding in Column 2 the geographic variables discussed above does not change the pattern. The only additional finding is that groups located in rugged regions are also more dependent on pastoralism than agriculture. In Column 3, we verify that Muslim groups today live in homelands that display this particular type of land use, i.e., a land allocation skewed against agriculture and in favor of pastoral activities.

Table 5 reports OLS estimates associating the relative importance of trade with distance to trade routes. Observations are at the level of a historical society, the sample is the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa). In all specifications the dependent variable is the (log of 1 plus) share from trade in subsistence measured as reported in the Standard Cross Cultural Sample (SCCS). Column (3) excludes societies that were documented by ethnographers before 1750 (Babylonians, Hebrews, Khmer, and Romans).

Is it the case that groups residing in habitats where farming today is limited and herding significantly more common had a similar lopsided type of subsistence in the pre-industrial era? This is what we ask in Column 4 where the dependent variable is the log ratio of the share of subsistence derived from animal husbandry over agriculture as recorded in the Ethnographic Atlas. Groups that today allocate more of their land towards pastoralism also used to derive more of their livelihood from similar activities in the past, suggesting the persistence in the structure of production across groups.

In Columns 5 to 7, we replicate the pattern shown in Columns 1 to 3 with the difference being that on the left hand side of the equation, instead of the contemporary land allocation, we use the log ratio of the historical subsistence share from animal husbandry relative to agriculture. Groups residing in homelands of limited potential for agriculture dotted with few pockets of fertile land also used to obtain more from herding and less from agricultural products in the pre-colonial era. Adding the geographical covariates in Column 6 reveals that the presence of desert and of regions with irrigation potential also skew subsistence towards animal husbandry. Finally, in Column 7, we show that indeed Muslim groups are those that historically were more dependent on pastoralism and less on farming, corroborating one of the long-standing themes in the environmental history of Islamic Eurasia and North Africa, namely, the interface between the steppe and the sown ( Mikhail, 2012 ).

In this environment where each area specializes in its comparative advantage (farmers on the fertile pockets and herders on the relatively arid ones), a larger geographical Gini coefficient may correspond to larger potential gains from trade. Richerson (1996) , for example, observes that “despite the emphasis on animals, most herders are dependent on crop staples for part of their caloric intake … procured by client agricultural families that are often part of the society and the presence of specialized tradesmen that organize the exchange of agricultural products for animal products.” This suggests that an exchange economy may be more vibrant within a community of many herders and few farmers. To shed light on this conjecture, we rely on the Standard Cross Cultural Sample (SCCS). Specifically, in Column 8 of Table 6 , we ask whether societies relying more on pastoralism relative to agriculture also derive more of their subsistence needs from trade; across the 186 ethnographic societies worldwide, this is indeed the case. Overall, the results in Table 6 reveal how the specific geographic endowments of Muslim homelands give rise to a distinct specialization pattern: a pastoral economy with few farmers where trade is important.

Why Ecological Similarity to the Arabian Peninsula Matters for the Spread of Islam

At first blush, showing that Muslim regions are ecologically similar to the birthplace of Islam, i.e., the Arabian peninsula, is consistent with various interpretations.

First, Michalopoulos (2012) argues that cultural groups have location-specific human capital derived from the type of geography they inhabit. Hence, when members of such groups leave their group’s homeland they are likely to target regions that are productively similar to their ancestral territories to ensure transferability of their skills. For example, early farmers and pastoralists moving out of the Fertile Crescent on the eve of the Neolithic Revolution follow this pattern of dispersal, i.e., farmers moving to land suitable for agriculture and herders targeting landscapes appropriate for animal husbandry. One may apply a similar reasoning to the diffusion of Islam. Since the productive toolset of early Muslims was fine-tuned to the arid landscapes of the Arabian Peninsula, seeing Muslims migrating to lands similar to their ancestral regions can be easily rationalized.

Second, Bulliet (1975) convincingly argues that one crucial element for understanding the spread of Muslim empires is the use of the camel that provided the Arab armies a military edge over their rivals. So, terrains suitable for deploying the camel would be more easily conquered whereas others would remain beyond the reach of Muslim rulers. Chaney (2012) shows empirically how a desert ecosystem is indeed predictive of the Arab conquests and Muslim adherence across countries today.

Both of these arguments are very relevant for understanding the spread of Islam in places that experienced either a Muslim conqueror and/or a significant influx of Muslims. Nevertheless, in many of the cases discussed in the historical section, Islam was often voluntarily adopted by the local rulers in absence of significant Muslim population movements. What arguments may then rationalize the voluntary adoption of Islam across geographically unequal regions? Below we offer some tentative explanations.

Islam, Trade, and Unequal Geography

We offer two complementary accounts that high-light the pro-trade stance of Islam. The first derives from the observation that historically within geographically unequal societies trade is likely to play an important role for subsistence (see Column 8 of Table 6 ). Hence, to the extent that Islam offered an institutional framework promoting exchange, groups across geographically unequal territories would have an added incentive to convert. Several Islamicists have stressed the pro-trade elements of the Muslim institutional complex. According to Cohen (1971) , “[Islam is a] blue-print of a politico-economic organization which has overcome the many basic technical problems of trade.” Trade called for new types of economic organization that required stronger authority ( Davidson, 1969 ). An important advantage of Islam with respect to previous arrangements was the fact that it offered a powerful ideology with built-in sanctions that created non-material interest in holding to the terms of contracts ( Ensminger, 1997 ). This common platform allegedly generated trust and contributed to the reduction in transaction costs while doing business with fellow Muslims.

Second, in our companion paper, Michalopoulos, Naghavi, and Prarolo (2016) , we advance theoretically a related hypothesis where the Islamic economic rules arise to mitigate social tensions across Arabia’s tribes exposed to long-distance trade opportunities during the 7th century CE. In a nutshell, we argue that trade diversion over Arabia created new potential economic benefits for the scattered oases by transforming them to trade hubs providing services to the trading community ( Watt, 1961 ). Caravans, however, for thousands of miles were constantly exposed to raids by the Bedouins, who made up a considerable fraction of the population at that time ( Berkey, 2003 ). In this historical backdrop, we hypothesize that Islamic rules were devised in response to the costly nature of predation between the Bedouins and oasis dwellers, offering a framework whose redistributive principies safeguarded exchange over numerous and heterogeneous tribal territories ( Bogle, 1998 ). 17

This view of Islam as an institutional package engineered to allow the flourishing of long-distance trade across unequally endowed regions generates an auxiliary prediction: Islam should be able to gain a hearing more readily across unequal territories close to trade routes. Empirically, this can be tested by adding the interaction between distance to trade routes and ports and the degree of geographic inequality. Columns 1 and 2 of Table 7 are country-level regressions and Columns 3 and 4 focus on ethnic groups within countries. Across both units of aggregation the interaction term enters with a negative sign and it is statistically significant. 18 The point estimates in Specification 1 suggest that the effect of land inequality on Muslim adherence across countries becomes insignificant for countries farther than 650 kilometers from the trade routes as of 600 CE, pointing to the differential incentives to convert to Islam among geographically unequal regions in the vicinity of historical trade routes.

Table 7 reports OLS estimates associating the share of Muslims with geographical variables. Observations are at the level of countries (columns 1 and 2) or ethnic groups (columns 3 and 4). The sample is the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa). In columns 1 and 2 the dependent variable is the share of Muslims in 1900 across countries from McCleary and Barro (2005), while in columns 3 and 4 the dependent variable is the share of Muslims across ethnic groups from the World Religion Database (WRD). Controls are Distance to Mecca, Distance to the Coast, Absolute Latitude, Ln Average Land Quality, Ln Land Area, Ln Ruggedness, Irrigation Potential Indicator and Presence of Desert Indicator.

The Supplementary Appendix gives detailed definitions, data sources and summary statistics for all variables. Columns 1 and 2 (3 and 4) include a set of continental (country) fixed effects. Standard errors, in parentheses, are robust to heteroscedasticity (columns 1 and 2) and clustered at the country level (columns 3 and 4). ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Although the decline in the predictive power of inequality in agricultural endowments farther from trade routes is consistent with the proposed view that Islamic rules were better suited for geographically unequal communities close to the trade network, it is far from a proof. To establish that converting to Islam indeed facilitated trade and changed the groups’ institutional framework – increasing redistribution and mitigating conflict – one would need data before and after Islamization. Cross-sectional variation only cannot shed light on whether converting to Islam changed the underlying institutional structure, or if groups that already had traits similar to what the Islamic scriptures prescribed found it easier to become Muslim. Taking these qualifiers into account in the Appendix we show that Muslim groups are different from non-Muslim ones in some of their institutional and societal arrangements. Specifically, in Appendix Table 4 we show that Muslim societies as recorded by ethnographers in the Old World are more likely to be politically centralized, harbor beliefs in moral gods, and follow equitable inheritance rules. Moreover, a strong link between an unequal geography and social stratification is present across non-Muslim groups but muted across Muslim ones.

5. Conclusion

In this study we examine the historical roots of Muslim adherence within as well as across countries. First, we digitize and combine a multitude of historical sources, to construct detailed proxies of ancient, pre-Islamic trade routes, harbors, and ports and show that regions in the vicinity of such locations are systematically more likely to be Muslim today. We view this finding as offering large-scale econometric support to a widely held conjecture among prominent Islamicists like Lapidus (2002) , Berkey (2003) , and Lewis (1993) , and complement this empirical regularity with historical accounts illustrating the importance of trade contacts in the process of Islamization of various prominent locations in Africa and Asia.

Second, we establish that Muslim communities tend to reside in habitats that are ecologically similar to those of the Arabian Peninsula, the birthplace of Islam. Specifically, we show that Muslim homelands are dominated by arid and semi-arid lands where animal husbandry is the norm, and dotted with few niches of fertile land where farming is feasible. Overall, a poor and unequal distribution of agricultural potential predicts Muslim adherence. We discuss the various mechanisms that may give rise to this phenomenon and offer evidence consistent with the view of Islam as an institutional package appropriate for societies residing along unequally endowed regions in the vicinity of trade opportunities.

The empirical analysis is conducted across countries and across ethnic groups within countries. Exploring within-country variation is crucial in our context given the intimate relationship between country formation and religious identity. Across both levels of aggregation, there is a robust link between proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes, geographic inequality, and Muslim representation. The identified pattern is unique to the Muslim denomination and it obtains for regions that historically have not been part of a Muslim empire. Overall, the empirical analysis highlights the prominent role of history in shaping the contemporary spatial distribution of Muslim societies.

We view these findings as a stepping stone for further research. For example, focusing on specific regions where historical data may be available, one may explore time variation in the speed at which Islam made inroads to the respective communities. Moreover, one element we do not touch upon is why religious beliefs – once adopted – persist over time. Insights from the rapidly growing theoretical and empirical literature on the persistence of beliefs and attitudes may shed light on this phenomenon (see Bisin and Verdier, 2000 ; and Voigtlander and Voth, 2012 ). Finally, having identified some of the forces behind the formation and spread of Islam, one might examine the economic and political consequences for the short-run and the long-run development of the Muslim world (see Michalopoulos, Naghavi, and Prarolo, 2016 ). We plan to address some of these issues in subsequent research.

Table 6 reports OLS estimates associating (contemporary and historical) measures of dependence on pastoralism and agriculture with land inequality, adherence to Islam and other historical and geographic variables. The dependent variable in columns 1 to 3 is the log ratio of pastoral to agricultural lands from Ramankutty et al., 2008. The log ratio of historical subsistence of pastoral to agricultural share, from Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas is the dependent variable in columns 4 to 7 and the (log +1) share of subsistence from trade from the SCCS dataset in column 8. Observations are at the ethnic group level in columns 1 to 7 and at the level of historical societies in column 8. The sample used is the Old-World part of the Ethnologue (columns 1 to 3), its intersection with the Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas (columns 4 to 7) and all groups in the Standard Cross Cultural Sample in column 8.

The Supplementary Appendix gives detailed definitions, data sources and summary statistics for all variables. Columns 1 to 7 include a set of country fixed effects with errors clustered at the country level in parentheses, while those of column 8 are robust to heteroscedasticity. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Appendix table 1 -.

Appendix Table 1, Panel A, reports summary statistics for the main variables employed in the empirical analysis at the county level. Panel B gives the correlation structure of these variables.

The Supplementary Appendix gives detailed variable definitions and data sources.

Appendix Table 2 -

Appendix Table 2, Panel A, reports summary statistics for the main variables employed in the empirical analysis at the ethnic group level. Panel B gives the correlation structure of these variables.

Appendix Table 3 -

Appendix Table 3 reports OLS estimates associating measures of Muslim adherence with geographical variables. Observations are at the level of countries (columns 1 to 3) or ethnic group (columns 4 to 6), the sample is the Old World (Europe, Asia and Africa). In column 1 (4) the dependent variable is a dummy equal to one if the share of Muslim in the country (ethnic group) in 1900 (2005) is greater than 50%, from McCleary and Barro (2005) (World Religion Database). In columns 2 and 3 the dependent variable is the share of Muslim population in 1900 measured at country level, while in columns 5 and 6 the dependent variable is the share of Muslim population in 2005 at the ethnic group level. Included controls are Distance to Mecca, Distance to the Coast, Absolute Latitude, Ln Average Land Quality, Ln Land Area, Ln Ruggedness, an Irrigation Potential Indicator and the Presence of Desert Indicator.

The Supplementary Appendix gives detailed variable definitions, data sources and summary statistics for all variables. Columns 1 to 3 (4 to 6) include a set of continental (country) fixed effects. Standard errors, in parentheses, are robust to heteroscedasticity (columns 1 to 3) and clustered at the country level (columns 4 to 6). ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

Appendix Table 4 -

Appendix Table 4 reports OLS estimates associating Muslim adherence across groups to various societal traits and geographical variables. In column 1 the dependent variable is the degree of jurisdictional hierarchy beyond the local community level. In column 2 the dependent variable is a dummy reflecting whether the local gods are supportive of human morality. In columns 3 to 5 the dependent variable is an indicator whether a group is socially stratified and in columns 6 and 7 the dependent variable reflects whether there is egalitarian inheritance with respect to movable and land property, respectively. In column 4 (5) the sample is restricted to ethnic groups with a share of Muslim population above 95% (below 10%). Observations are at the ethnicity level and the sample comprises of groups in the Old World for which we have created a correspondence between the Ethnologue and the Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas. Controls are Absolute Latitude, Ln Average Land Quality, Ln Land Area, Ln Ruggedness, an Irrigation Potential Indicator and Presence of Desert Indicator.

The Supplementary Appendix gives detailed variable definitions, data sources and summary statistics for all variables. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the country level. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

1 Traslation by Dr. Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din Al-Hilali and Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan in 1999.

2 See Barro and McCleary (2006a , 2006b ) for an overview and Barro and McCleary (2003) , La Porta et al. (1997) , Martin, Doppelhofer, and Miller (2004) , and Pryor (2007) , among others for mixed evidence of the impact of religion on economic indicators.

3 All distance measures are constructed in the following manner. We generate a grid of 0.5 by 0.5 decimal degrees and intersect the resulting cells with the country and homeland boundaries. We then calculate the distance from the centroid of each cell within the country/homeland to the nearest feature. To arrive at a single distance term for each unit of aggregation, we take the mean value of the distances across the cells that fall within the country/ethnic homeland borders. This procedure is more accurate than using only the country’ or homeland’s centroid. Moreover, using the minimum or the maximum distance instead of the mean distance to the attributes of interest delivers noisier coefficients.

4 WRD classifies as Muslims the followers of Islam in its two main branches (with schools of law, rites or sects): Sunnis or Sunnites (Hanafite, Hanbalite, Malikite, Shafiite) and Shias or Shiites (Ithna Ashari, Ismaili, Alawite, and Zaydi); also Kharijite and other orthodox sects; reform movements (Wahhabi, Sanusi, Mahdiya); also heterodox sects (Ahmadiya, Druzes, Yazidis); but excludes syncretistic religions with Muslim elements and partially Islamized tribal religionists.

5 Hsu et al. (2008) show that the country level estimates for Muslim representation in WRD are highly correlated (above 0.97) with similar statistics available from World Values Survey, Pew Global Assessment Project, CIA World Factbook, and the U.S. Department of State. At the ethnic group level, there are no comparable statistics.

6 For some language groups in WLMS (2006) the WRD offers information at the subgroup level. In this case the religious affiliation is the average across the subgroups.

7 In the online Appendix , we discuss in detail the components of the land quality index and present the sources of the data used in the empirical analysis.

8 We focus on countries with at least three regional observations of land quality to ensure that our findings are not driven by countries with limited regional coverage. Using the Muslim representation in 2000 as the dependent variable, the coefficients of interest are larger and more precisely estimated. Presumably this is because earlier estimates of religious affiliation are noisier.

9 We follow Bentzen, Kaarsen, and Wingender (2016) and define the irrigation potential of an area as land that is classified in irrigation Impact Class 5. Impact Class 5 are those cells where irrigation can more than double agricultural yields. Out of the 127 countries, 72% have some irrigation potential whereas 28% of countries feature no such cells.

10 We follow Hsiang (2013) to visually display the uncertainty of the regression estimates in Figures Figures3 3 and and4 4 .

11 Similar to the cross-country regressions, we focus on ethnic groups with at least three regional land quality observations. Using all ethnic groups irrespective of the underlying geographic coverage does not change the results.

12 The results presented here are OLS estimates with the standard errors clustered at the country level. Adjusting for spatial autocorrelation following Conley (1999) delivers more conservative standard errors.

13 The SCCS comprises ethnographically well-documented societies, selected by George P. Murdock and Douglas R. White, published in the journal Ethnology in 1969, and followed by several publications that coded the SCCS societies for many different types of societal characteristics.

14 The Arabian Peninsula consists of the following 9 contemporary countries: Yemen, Oman, Iraq, Jordan, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

15 Unlike the SCCS dataset, Murdock’s Ethnographie Atlas does not have information on trade-related traits.

16 Note that the number of groups in Columns 1 to 3 is 2, 845 instead of the 3,181 covered in Table 3 . This is because for 336 linguistic homelands the allocation of land either towards farming or towards pasture in 2000 is 0 so the log of their ratio is not well defined.

17 The link between the structure of production, institutional formation and religion can be readily glimpsed in the works of Ibn Khaldun (1377) and Marx (1833 [1970]) . Ibn Khaldun (1377) notes that “it is the physical environment-habitat, climate, soil, and food, that explain the different ways in which people, nomadic or sedentary, satisfy their needs, and form their customs and institutions,” whereas Marx (1833 [1970]) highlights that religion, like any other social institution, is a by-product of the society’s productive forces.

18 Note that when we use the trade network before 1800 CE the direct effect of distance to trade routes also reflects reverse causality. Nevertheless, irrespective of who set up the routes, we may still explore whether it is unequally endowed regions that are differentially impacted.